Category Archives: History

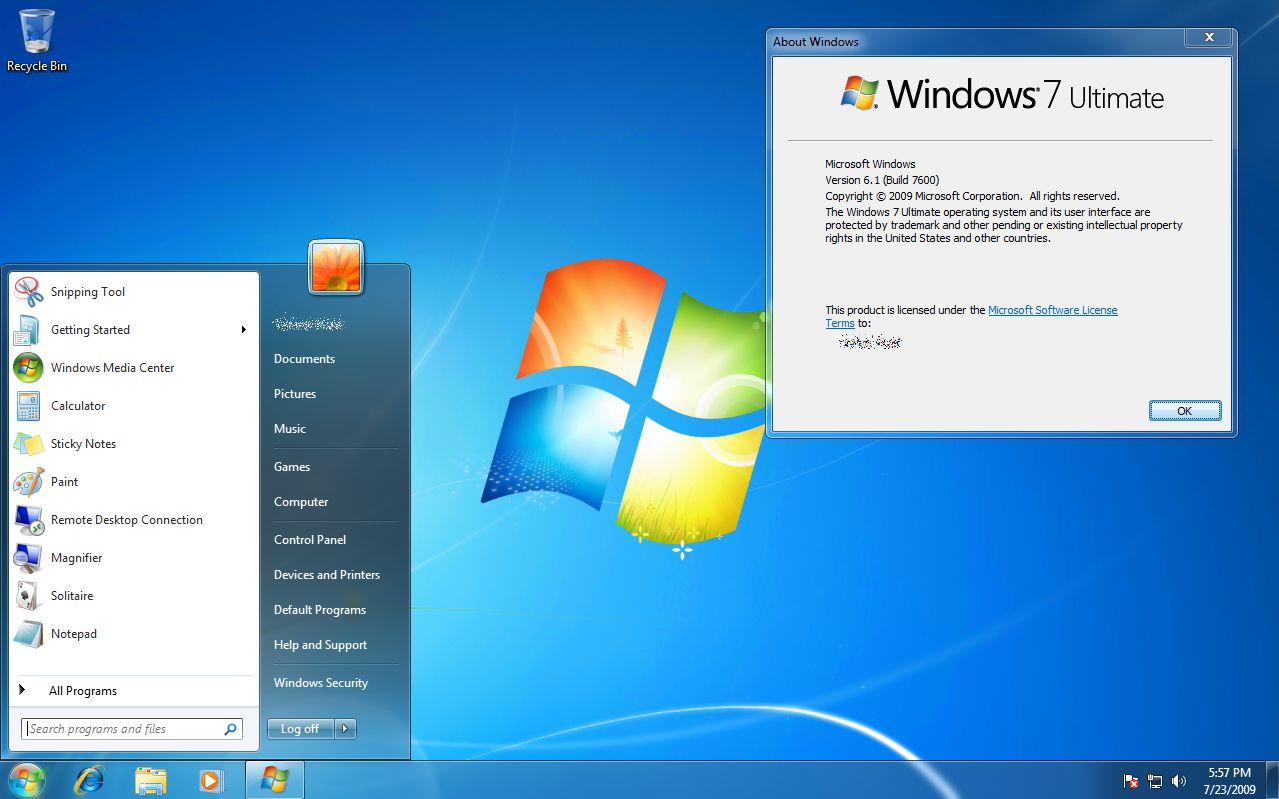

Support for Windows 7 ends today

It is a sad day, as Microsoft is officially ending updates and security patches for Windows 7, the popular OS still being used by a large majority of PCs. Windows 7’s popularity stems in part from the large-scale rejection of Windows Vista (which I never had a problem with, personally), itself an apparent upgrade from Windows XP, which was also widely hailed and widely used.

This will cause some problems for people, small businesses and even large corporations that still heavily rely on the OS, as they will no longer be able to secure the platform after today. The fact that Microsoft is willing to provide continuing security updates for $25 per machine to start is not an effective IT strategy for a business, plus you can use Microsoft’s own upgrade tool to upgrade your machine for free. While we all loved Windows 7, it really is time to move on.

While sad, it’s also understandable, as companies must evaluate where they should delegate resources, especially when they have so many previous versions of Windows. On the other hand, considering the user base is still so strong, almost 33 percent right under Windows 10’s 47 percent, one might think they would still consider it an important horse in the stable, but people aren’t going to upgrade if you don’t give them good reason. Plus, I don’t see any major new versions of Windows (Windows 11? 14?) being released anytime soon, now that Microsoft is moving past CEO Satya Nadella’s ‘Mobile-First, Cloud-First” strategy into “Everything AI,” which still embodies some of the previous mantra.

Microsoft has, in my opinion, made great strides lately in terms of opening their platforms, becoming more accessible, and playing nice with other companies. Plus, you could always run Windows 7, or any other Windows version, in a virtual machine and never have to forget the glory days of the last great operating system.

Plus, you know it will end up available like this or this someday anyway.

Returning Home: World of Warcraft Classic Comes Online

On August 26th, fans of the original World of Warcraft (henceforth referred to as WoW), and those who are just curious to see what all the hubbub is about, were finally able to re-experience the original game as it was when it first came online back in 2004, now colloquially known as ‘vanilla’. And boy did Blizzard deliver, complete with massive queues, disconnects, and crowding. But they have also provided what many people have been asking for for many years: The authentic and original WoW experience.

World of Warcraft was first released in 2004, a Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game (MMORPG) in the vein of Everquest and Ultima Online before it. However WoW streamlined the gameplay process and created something accessible, that anyone could play, and eased players into the experience without being overwhelming. It was an instant, massive hit, and has continued to be a juggernaut even to this day. Attempts to topple it, even using popular franchises with similar gameplay such as Age of Conan and Star Wars Galaxies, couldn’t come close to WoW’s success.

In the game, there are two main factions: The Horde, comprised of Orcs, Trolls, Tauren, and the Undead, and the Alliance, comprised of Elves, Gnomes, Dwarves and Humans. Depending on your race, you could be one of several classes: A paladin, mage, warlock, rogue, warrior, priest, druid, hunter, or shaman, each with their own unique abilities and approaches to gameplay.

As the years went on, WoW evolved. What started out as a world with two continents, eight races, nine classes and a tight story to tell, ended up as what many consider to be a mess in terms of overly-streamlined gameplay (e.g.: quest markers and highlighted objectives / objects), homogeneous races and classes (e.g.: many classes were limited to certain races, but now that’s generally not the case; anyone can be anything. Another example: Undead could ‘breathe’ underwater, now anyone can breathe underwater for a comically long time), and simplified specializations that don’t allow for really exploring a particular class.

Combine that with the original story of the Horde V. the Alliance morphing into them working together and sharing quests and zones, a rambling main story with red herring side quests and endless grinding with things such as daily quests, as well as a confusing world structure (A new capital city, Dalaran, now has two separate locations in the game: One in Northrend and one in the Broken Isles. It’s the same city, but in two places, although there is lore for that), and people started to get weary.

Not that it was all bad, mind you. The ‘Mists of Pandaria‘ expansion, which introduced a continent known as Pandaria based on Chinese lore, along with a race of humanoid pandas known as the Pandaren, and the new class of monk, was very well received. Additionally, flying mounts and pets of many types became available as nice additions. But overall, the gameplay itself, the core experience, lacked.

Mists of Pandaria

While all this was going on, something known as private servers began to appear. These were privately run WoW servers that there recreated that original version of the game as it was when it was first released. There was no charge, and people flocked to them. The largest was Nostalrius, which at its peak had, according to Wikipedia, 800,000 subscribers and 5000 – 8000 concurrent players. Blizzard hit them with a cease & desist order, but the coverage of that was severe and intense, and it appeared that Blizzard noticed. I myself played on Nostalrius, and wished it to continue. An interesting aside about it is that when I dowloaded the client, which had to be done as a torrent, I was immediately – while the download was still happening! – sent an email from Cox telling me they had received an official complaint about my IP from Blizzard stating I was pirating the game.

But I digress. Blizard may have noticed, but also said very publicly during a live conference, that ‘you may think you want vanilla WoW, but you don’t.’ They had to eat crow on that, but they did so with grace and humility, and I respect them for being good about it.

They eventually announced that would be creating a classic WoW experience, and it finally came online August 26th, 2019.

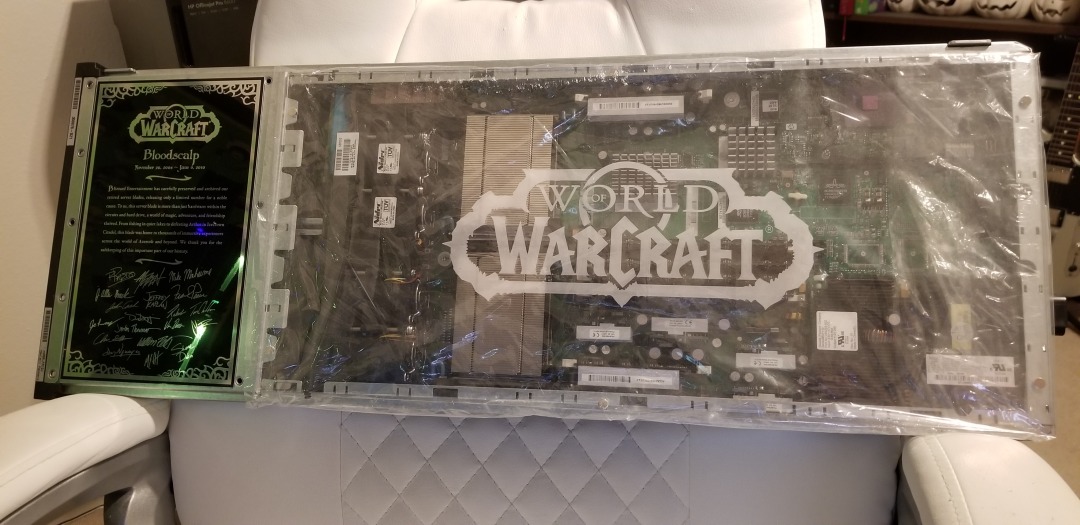

I was excited for this too. Seeing the announcement of original WoW gave me chills. I loved original WoW, and was even in the beta so many years ago. It’s strange, because as I would read magazine articles and online posts about it, I didn’t have much interest. I heard the beta was coming and thought ‘why not?’ Well, it turned out to be lifechanging. I’ll never forget creating my first character, an undead warlock of course and of course on the server named ‘Bloodscalp,’ and venturing out into Deathknell, the undead starting zone. The purplish tint of my shadowbolt, the civilized undead, the unique, not-quite-cartoony but surprisingly colorful and detailed environments, and as I would eventually learn the incredible backstory and unique races, including the Native-American styled large bipedal bovines known as Tauren, a really unique offering for a game of this type. So much did I love it that I bought the Bloodscalp server on which I used to play when they were retired for an upgrade.

Eventually, though, after years of playing, it was sadly no longer the game I remembered. I stopped playing for a good number of years after I heard someone yelling in general chat that if they wanted to group with him for a raid, they ‘SHOULD LINE UP FOR GEAR CHECK’ and ‘DO NOT WASTE MY TIME’ and ‘KNOW YOUR ROLE AND DON’T ASK QUESTIONS.’ Remembering how the game was when it started, how everyone was incredibly helpful and pleasant, that one jackass really discouraged me, and he wasn’t even talking to me. That was after a couple of expansions had released, and for those of you familiar with the game it happened in Shattrath, a city and storyline I just could not get into anyway, and I logged off that moment and didn’t play again for five years at least.

Not only were these hardcore players becoming more common in current WoW, enemies became easy to defeat, everything is signposted, there’s no sense of accomplishment or earning your way, and the story, for me anyway, was just confusing and I couldn’t figure out what was going on. Original WoW does not hold your hand in any way; it’s unforgiving, and expects you to read the quest text and figure out what to do. When it was announced, to paraphrase an infamous in-game proclamation, I was definitely prepared.

There was some drama leading up to the event that I myself was caught up in. It was announced that two weeks ahead of release, players could log in and create / name their characters. I have characters I have played with for FIFTEEN YEARS. When I logged in to create my characters on the Whitemane server, which was my server of choice as it is PvP and PST, I was hit with a 45 minute queue and by the time I managed to get in all my names were already taken! Wheels was the name I desperately wanted, and I made numerous posts on the classic WoW reddit sub and in the Whitemane server sub as well asking if the person who had it would be willing to trade or even sell, but no luck. I ended up with Kneecap, which I actually like, but it’s not Wheels.

Well, once the servers came online, while waiting in the ENORMOUS Whitemane queue (see image below), I just happened to also be in the classic WoW Discord watching the live feed of people trying to get in drama when I saw a post shoot by stating Blizzard would be bringing three new servers online, including a PST PvP server named Smolderweb. Smolderweb! I liked Whitemane, but Smolderweb was far more badass than I could have hoped, so I waited. Waited…waited…and the second it came online I pounced, created all my characters, and got all the names I wanted! I couldn’t believe my luck. There was also no login queue, I got right in and grouped up with some great people and had a blast running around the troll / orc starting area. Players even lined up for specific quest targets in a very orderly and polite way. Everything ran very smoothly, there was absolutely no lag, and I couldn’t have been happier with the experience.

To be fair, I saw posts that showed the Alliance also lined up for their quest objectives, so it was good all around.

I find it telling that even though this is no longer WoW easy mode, and that everything has to be worked for (your first ten levels will be hard, until your class specializations start to kick in, and then it will be less hard but still hard), I’ve had the most fun I’ve had in WoW for many, MANY years, and I’m very glad to be back in the world that I left so long ago.

The Lawnmower Man, and Vintage CGI

Inspired by a couple of Reddit forums to which I am subscribed, VintagePixelArt and VintageCGI, and being a fan of all things historical as it pertains to technology, I uploaded to the latter a brief scene from the 1992 CGI-fest movie The Lawnmower Man,’ supposedly about a guy who killed people using a lawnmower. Based on a book of the same name by Stephen King, King sued to have his name removed from the movie as it bore – barring one minor scene – absolutely no connection to the book. Rather, the movie was used as a vehicle to show off what the state of CGI, or Computer Generated Imagery, was at the time. The 30-second plotline is Dr. Angelo, a scientist funded by a shadowy company, is researching whether or not Virtual Reality can be used to enhance the human cognitive capabilities, or even unlock potential powers. He recruits Jobe, who helps around the grounds at local church and suffers from cognitive disabilities, and straps him into a complicated VR setup that turns Jobe into a god who ends up not acting very godlike.

The movie was fun, but the real purpose of the thing was to show off what the state of the art was in terms of CGI at the time, and also present what was at that time a still-unknown technology: Virtual Reality. Here is the clip I uploaded; I just clipped the scene out of the movie file:

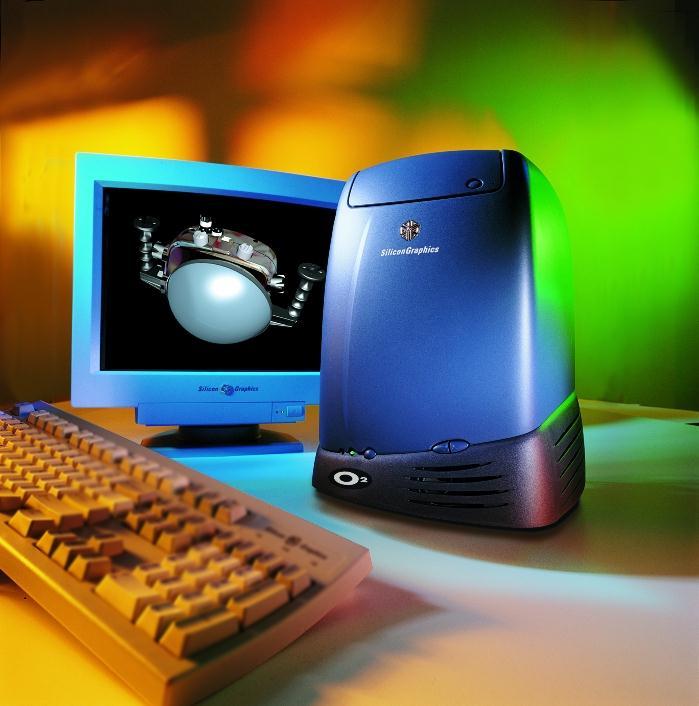

In 1992 when the movie was released, commercial-grade computer generated imagery was created primarily on Silicon Graphics workstations, which at the time were the powerhouse machines of the day. Now, we have laptops with more computing power, but back then SGI workstations were the top of the line pro setup, and everyone from movie studios to science labs to government agencies wanted them for their ability to do everything we take for granted today: Simulations, animations, visual manipulation, prediction, etc.

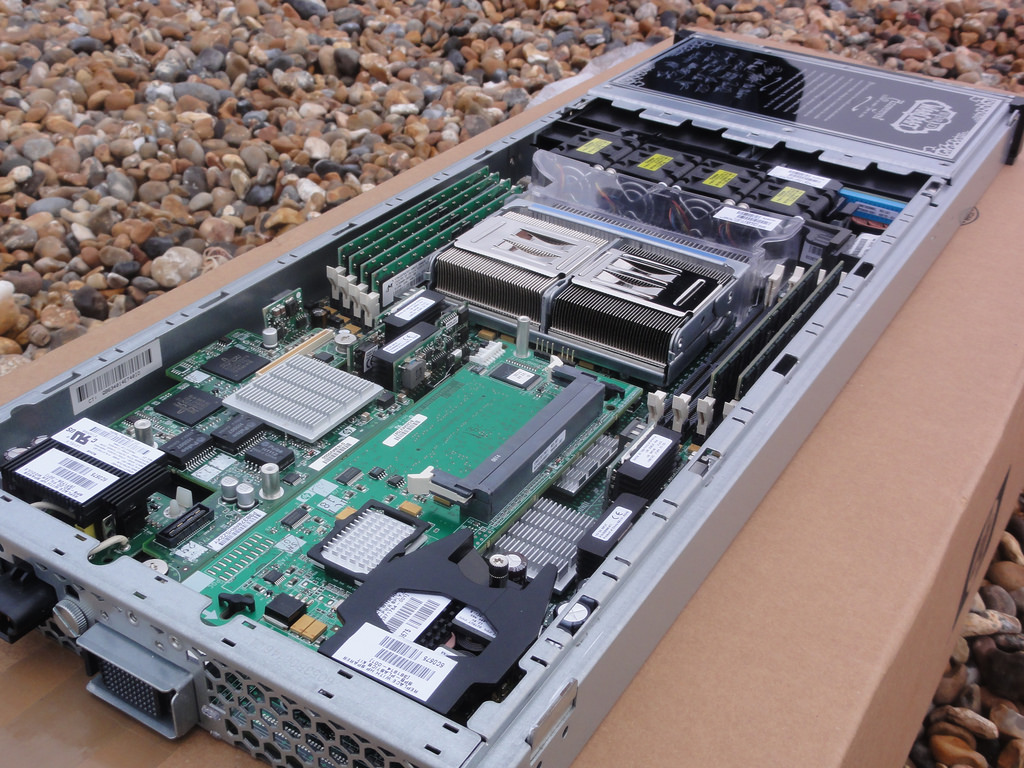

They didn’t necessarily use special processors or OSs, in fact many of them ran on Intel processors and Windows NT, although other versions ran on UNIX. The difference was their proprietary hardware architecture, and compared to what commercial PCs had at the time, the SGIs were far more powerful. $4,000 would get you their low-end model: a Pentium II-powered box with 128MB of RAM. You read that right. This is a Linux box SGI, the O2:

Appropriately, the former SGI building in Santa Clara now holds the Computer History Museum.

Movies were used as vessels to show off incredible, and sometimes not so incredible, computer imagery quite often. The absolute king of the hill in this area is the original TRON (1982), which not only used CGI but many other tricks as well, and gave us a glimpse of what life might be like inside a machine when computers and technology were still largely undiscovered country but arcade machines had already left an indelible mark. A perfect example of TRON’s influence is in the famous light cycle scene.\

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-BZxGhNdz1k

The first ever use of CGI in a movie was all the way back in 1976’s Futureworld. This movie used a scene of a CGI hand that had originally been developed by Ed Catmull, a computer scientist at – wait for it – teh University of Utah (see below) who went on to create Pixar! Here’s the scene from Futureworld.

Computer capabilities in terms of imagery, visualization and rendering has been the fascination of many for a long time. One image has even gained celebrity status: The Utah Teapot. (Side note: I usually prefer not linking to Wikipedia, however the University of Utah’s own Utah Teapot page links there!).

The Utah Teapot, created in 1975 based on the need for a perfect shape, has since become the introduction to computer graphics, and has been featured extensively in other computer animated environments, with my personal favorite of course being its appearance in the animated sequence from The Simpsons’ Treehouse of Horror episode, titled Homer(3), in which Homer gets sucked into the horrific THIRD DIMENSION. You can see the teapot at 2:21 when Homer realizes he is ‘so bulgy.’ There are many other neat references in the scene. This scene was based on an episode of The Twilight Zone, a prophetic show in and of itself, called ‘Little Girl Lost,’ in which a girl is transported to the fourth dimension from the third.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=143&v=7824c5YAsEA

Because we didn’t have immediate access to the capabilities of technology back then, especially computer animation, seeing it was a revelation. This was capitalized on by a series of (originally) DVDs, later laserdiscs, titled ‘The Mind’s Eye (1990).’ The followups were Beyond the Mind’s Eye (1992), Gate to the Mind’s Eye (1994), and Odyssey Into the Mind’s Eye (1996). Each was about an hour long and contained a series of CGI vignettes set to music. These vignettes were created by graphics firms, advertising firms, and others, and often scenes created by different companies were woven together and set to music to tell a story.

I first saw a scene from The Mind’s Eye being displayed on a giant display TV in front of a store (I don’t even remember which store!) in Security Square Mall in 1990, and I was mesmerized. I should have been amazed by the TV, but it was the visuals on it that really blew me away. It’s not my favorite scene in the series, but it holds a special place in my heart for introducing me to the series and for telling a touching story to boot, about a bird and a fish that destiny has deemed will be together. A hopeful allegory for today. Here it is:

I can’t find any information about who actually created this animation, so if you know, please pass it on! You can also watch the entire movie on The Internet Archive.

My favorite scene from the Series is found on the Second release, Beyond the Mind’s Eye. This one is called ‘Too Far’ and contains multiple scenes from various artists, including what might be my favorite animated character ever, the once famous Clark. There’s a lot going on in this segment, and it’s a masterpiece of CGI of the time.

Now here’s where it all ties together: The CGI created for the Lawnmower Man was also included in scenes from Beyond the Mind’s Eye. Not only that, the movie’s CGI was created by Angel Studios, which would later become part of billion-dollar video game powerhouse Rockstar San Diego. See how it all comes together?

In the years that followed, machines like the Amiga and of course Macs and PCs overcame the need for dedicated workstations, although the term persists. And now easy access to all sorts of graphical capabilities is at our fingertips, with engines being able to calculate what we can see and what we can’t and render accordingly, or cast rays of light based on reflection and refraction, or apply textures to surfaces, and so on. But that’s what makes these creations so much more impressive; using the tools of the time, they still were able to create such magical animations.

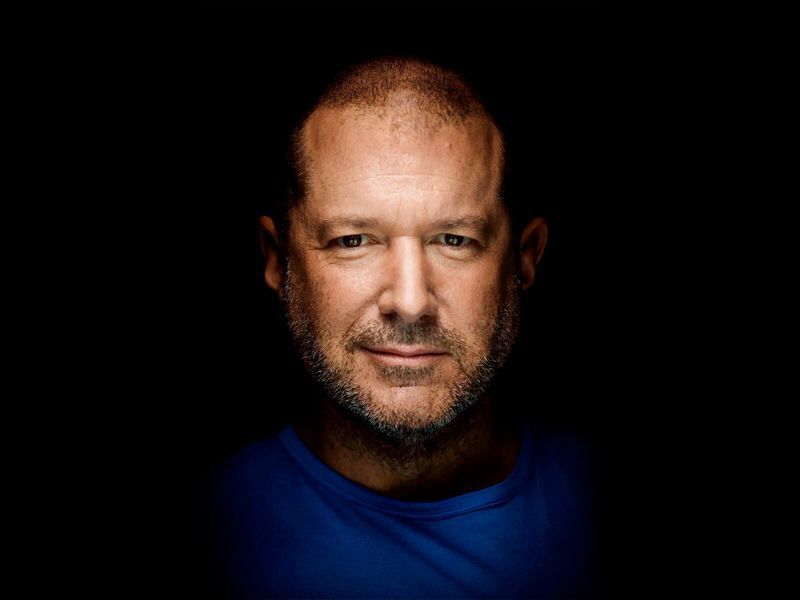

Jony Ive leaves Apple

As someone who teaches extensively about design as it intersects with technology, and is also a computer and technology historian, I am conflicted about Jonathan (Jony) Ive leaving Apple. Mainly because he’s not really leaving, however any sense of him doing so makes me think Apple will continue to move away from the designs for which it is so noted.

While he will no longer be part of Apple, he has decided to start his own design firm and will continue to contribute to and work with Apple. This seems like a very smart move, especially considering he was the creative force behind such behemoths as the Ipad, original and subsequent IMacs, everything in the IPod / IPhone line, Apple watch, and who could forget one of his first big projects, the TAM, or Twentieth Anniversary Macintosh, priced at an insane $7500 in 1997, but having many luxury amenities such as a leather wristwrest and no two being the same (none had the same startup chime or color, for example).

Not all of his ideas were a success; while the TAM was his first big contribution to Apple design, he had also worked on the Newton, which by the time he got involved was already flailing and clearly on its way out. In fact, it’s one of the first things killed off when Steve Jobs returned to save Apple. It was at the time of that return that Jobs asked Ive to stay on as a designer and help get Apple, who was in financial distress at the time, back on its feet. It’s well known that Jobs and Ive were aligned in terms of what design is and what it should be, and with the two of them working together the result is a company that is now one of, and often the, most highly valued companies not just in the world, but of all time.

In a bittersweet way, Ive’s leaving Apple signals the end of Steve Jobs’ influence in the company he helped found, which may be one of the reasons Ive has decided to now forge his own path. When Jobs returned to help the floundering company, and asked Ive to help him, a powerhouse was formed. With Jobs gone and Ive leaving, it is now the company that it is, and I fear for its future as it moves away from the design principles that made it what it is and into more services that may dilute its brand.

I have a deep and profound admiration of Apple, even as they seemed to have recently lost their way: A focus on subscription services and less of a focus on hardware and design, but they were the company that made computing and technology popular and sort-of accessible back in the day. Believe it or not, Apple, especially with their IIe line, was the computer to have for gaming and productivity, and you can still experience that through multiple online emulators such as VirtualApple.org, AppleIIjs, or using the AppleWin emulator and the massive disk image collection at the Asimov archive or Internet Archive.

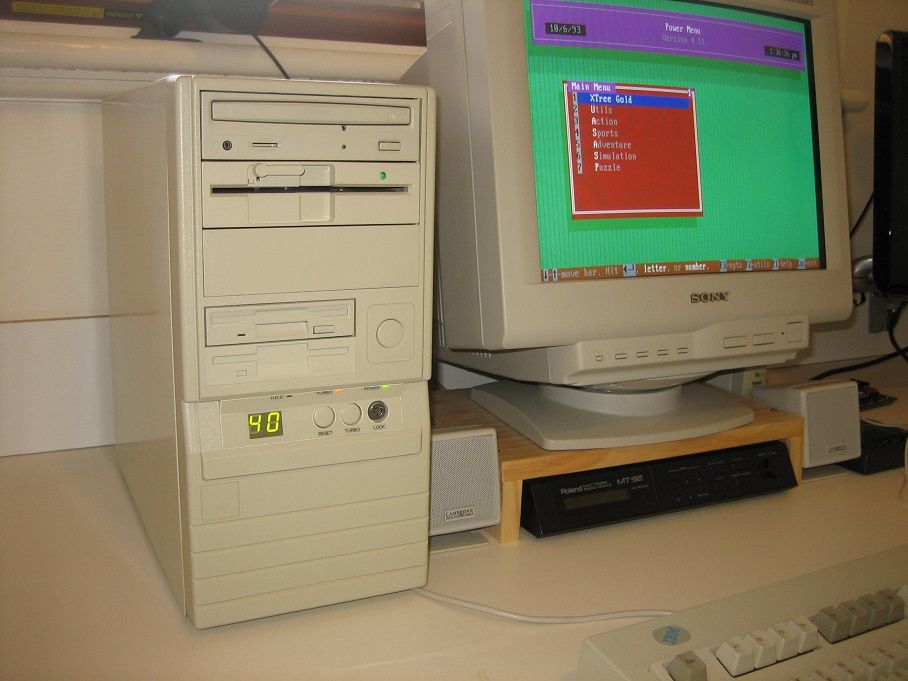

They were instrumental in bringing design to what was other fairly mundane technological designs. Indeed, PCs of the day were commonly referred to as ‘beige boxes,’ because that’s just what they were. Have a look (images sourced from the vogons.org message board about showing off your old PCs, and has many other great pictures).

Side note: Surprisingly, although I consider myself design focused, I don’t hate these. Probably because of nostalgia and the many fond memories I have of the days of manually setting IRQs and needing to display your current processor speed, but nostalgia powers many things.

Side note number two: I actually went to the same high school as both Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak; Homestead High in Cupertino.

So farewell to Jony and hopefully you give us many more outstanding designs in the future, farewell to the Jobs era of Apple as the company struggles creatively without him, and I am keeping hope alive that form and function in design will continue to reign.

A win for digital preservation

As many of you know, I am a big fan of older software and systems, even maintaining a small collection of vintage computer systems and software. Indeed, it is the software that is important, as hardware without software is just hardware, nothing more. Every piece of hardware needs a killer app to run on it, or people don’t buy the hardware in the first place. It’s why game consoles need to have a robust software lineup available at launch, or else risk being left behind for the entire generation.

Thing is, preserving physical copies of software is easy, procedurally, anyway. You have the physical software, and you digitize it while preserving the physical copy itself, and it could be a permanent record. of course, there are issues with maintaining the software in a runnable state, both for the digital version (are there suitable emulators available?) and clearly for the physical version, which is subject to all kinds of risks including environmental and technical. There is the issue of bit rot, an ill-defined term which generally refers to either a physical medium being unusable because as technology advances, the hardware used to read it becomes obsolete, or the general lack of performance of a physical medium overall due to the aforementioned environmental or other factors.

Even with physical copies, issues of the grey-area legality of emulators is always front-and-center, with the real focus being on ROMs. Nintendo recently shut down long-time and much-loved ROM site EmuParadise simply by threatening legal action. Curious, considering EmuParadise has been around so long, but now Nintendo wants to start monetizing its older IPs, and EP might put a bee in that bonnet. Also, ‘shut down’ isn’t entirely true: they didn’t shut it down but the site no longer hosts ROMs, and even though there is still a lot of information, the actual games being lost is a big problem. I have to go further out of my way to find ROMs, even for games whose companies, platforms, sadly even developers are long gone.

So why does this all come up now? Because we are in an age now where much of the software, data, and information we have is in digital form, not the physical form of old, and this leads to huge problems for historians and archivists such as myself. If something is only available digitally, when the storefront or host on which it is available goes down, how will we maintain an archived copy for future generations to see and experience? I have a Steam library with, at the time of this writing, over 300 titles that are all digital. there is no physical copy. So, just for argument’s sake, let’s say Steam closes shop. What happens to all those games? those VR titles? That one DAW? Will they just vanish into the ether? Steam claims if they ever shut down, we’ll be able to download them all, DRM free. But will we? As the best answer in that earlier link states, Steam’s EULA that all users are required to accept, states that their games are licensed, not sold. That may seem strange, but it has actually been that way for a long time. Even with physical games, you don’t actually own them and what you can do them outside of simply play them is exceptionally limited.

So how do we preserve these digital-only games? Whether a tiny development house creating an app, or a huge AAA title developed by hundreds of people: if the company shuts down or the people move on or whatever happens, how will we access those games in the future, 10, 20, 50 years from now?

This becomes even more of an issue when we have games with a back-end, or a server-side component. The obvious example is MMOs such as Everquest and World of Warcraft. What happens when their servers shut down and the game can no longer be played? How do we continue to experience it, even if for research or historical purposes? If the server code is gone, having a local copy of the game does us no good. As many MMOs and other online games continue to shut down, the fear is they will simply fade into nothingness, as if they never existed, but their preservation as a part of the history of gaming and computing is important.

Some brave souls have tried running what are called ‘Private Servers,’ which is server code not run, supported, or authorized by the developing company. Again, the most common example are World of Warcraft private servers you can join, which are not running the current code, but earlier versions which people often prefer and which brings up another interesting issue regarding the evolution of these digital worlds: Even if a game is still going strong, as is WoW, how do we accommodate those who prefer an earlier version of the game, in this case known as vanilla, meaning with the original mechanics, structure, narrative, and other gameplay elements that were present on launch but have since been designed far out of the game? Vanilla WoW is not officially offered although that will apparently be changing, but many private servers are immediately shut down via Cease and Desist orders from Blizzard, with one being shut down the day it came online after two years of development. Others manage to hang on for a while.

At the risk of going off on too much of a tangent, the reason I’m talking about this and why it has taken me six paragraphs to get to my point is that there has been a semi-wonderful ruling from the Librarian of Congress that essentially maintains an already-written rule that if a legacy game is simply checking an authentication-server before it will run, it’s legal to crack that game and bypass the check procedure.

Additionally, while that small thing includes the ability to allow legacy server code to run and be made accessible, it specifically can not be done so by private citizens, only a small group of archivists for scholarly / scientific / historic / other related reasons, and most importantly, the server code has to be obtained legally. That may be the biggest hurdle of all, as it is well known some companies sit on games and IP long after their market value has faded, preventing them from being released or even reimagined by the public. I’m hoping this is the beginning of a renewed push for legal support to archive and utilize legacy code and legacy server code to continue to preserve not just software titles of all types, not just games (and the new ruling includes everything), but the interim forms they took throughout the course of their development.

One additional note that surprises me even to this day: There is one online game that while very popular was eventually shut down by its parent company. That game was Toontown Online, and it was developed by Disney, a company well-known for aggressively protecting its IP. So it is especially surprising, that when an enterprising teenager who missed the world they had created decided to run a free private server, even renaming it Toontown Rewritten, Disney let it go! It has been up and running for a good number of years, has seen many improvements, updates and additions other than its terrible log-in client, and runs quite well. Here’s a screenshot of its current state, and as you can see it is still popular.

It still uses Disney-owned names and imagery, and has the unmistakable Disney aesthetic – there’s even a Toontown in Disneyland! If you want to see the proper way to handle this whole issue, once your game is done and abandoned, let an enthusiastic team who is passionate about the project and treats it with respect take over. It makes goodwill for you, a positive experience for them, and ensures your creation will continue to live on.

Happy Birthday TRS-80!

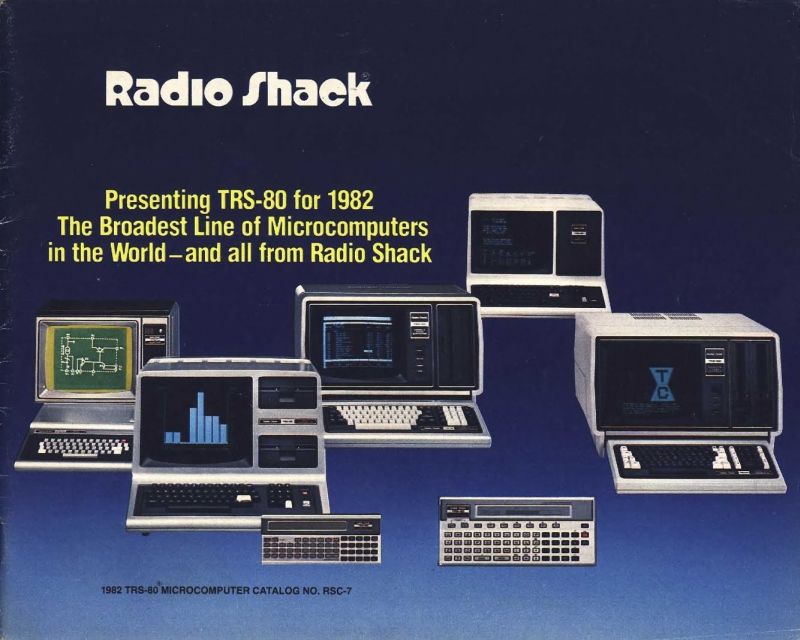

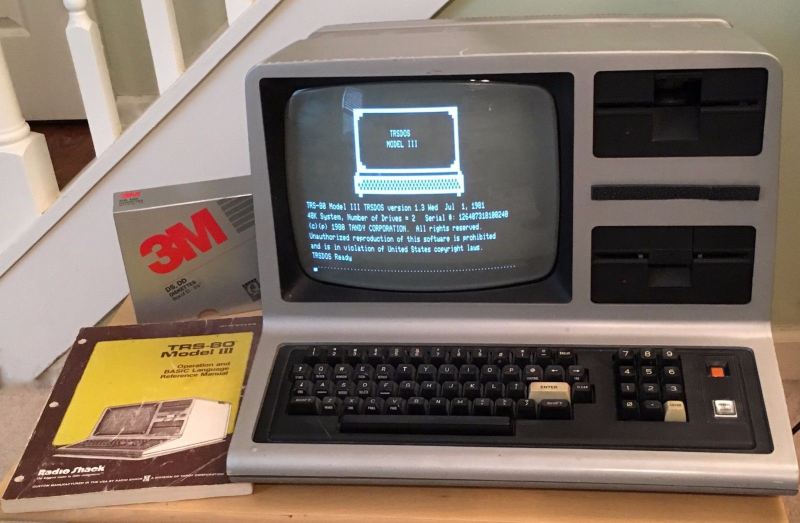

Today, August 3rd, is the 41st anniversary of the release of the Tandy / Radio Shack TRS-80 personal computer, originally released back in 1977 (Tandy was a leather company of all things, and bought out Radio Shack WAY back in 1962 – TRS is an acronym for Tandy Radio Shack). I have a personal place in my heart for this particular machine, the Model III specifically which is shown in the header image, but the whole line, which included pocket-sized, handhelds, portables, luggables, and multiple desktop models over the years, is easily one of my favorites.

You see, there is a trinity of devices and systems in the history of computing that just give me chills when I think about them, and along with the Commodore PET and Apple IIe, the TRS-80 is one of them. Although it wasn’t the first true PC I ever used – that would be the PET – it was the first on which I had significant exposure to what a machine could do. It was the machine of choice for a computer summer camp – don’t judge! – that I attended while but a wee lad. Using cassette tape as magnetic storage via an external cassette player often also bought at Radio Shack, we learned about computers and programming and wrote programs in line-number BASIC. They weren’t terribly sophisticated, but even at that young age, I managed to write a text-based adventure game in which you explored a haunted house solving what I thought were pretty well-thought out puzzles: I was most proud of the skeleton who was willing to help you, but only if you retrieved his missing golden-ringed femur which had been stolen by a dog – a golden retriever. I’m STILL proud of that one.

Even though it was colloquially referred to back then as the “Trash-80,” showing that system wars have existed for far longer than anyone would imagine, it was a surprisingly robust machine. Being the pre-GUI era, and even the pre-OS era, like the PET it came only with BASIC pre-loaded; there was no true operating system. An attempt was made to address that with the later release of TRS-DOS, although even that wasn’t a true operating system; it was merely a limited expansion of the capabilities of BASIC. The most efficient thing to do if you wanted to run programs was to buy them on cassette and load them into memory via the play button on a standard cassette player. If you wanted to save a program you wrote, you’d use the record function, but be sure to skip past the leader tape (a mistake I made once and never again).

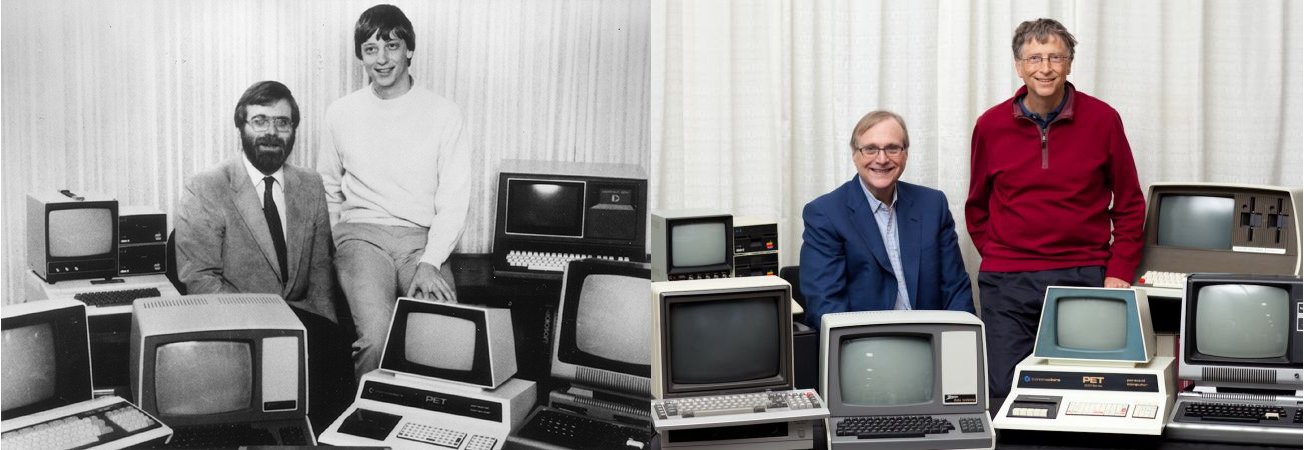

Oh, did I mention that much of the system code for the TRS-80 was written by Bill Gates? It’s true! In fact, here’s a neat side-by-side of Bill Gates and Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen in 2013, recreating a famous photo originally taken in 1981, in which they are surrounded by, among other things, an Apple, Commodore Pet, and TRS-80! These images were taken from a Forbes article about the event that’s interesting reading.

Versions of the TRS-80 were released and in operation up until around 1991, which is a pretty good lifespan for a PC line, especially one that was never considered much competition for the other powerhouse lines from Commodore, with the C64 still being the most successful personal computer ever made, or Apple, a company that’s still so successful it just became the first to have a trillion-dollar valuation. Meanwhile Radio Shack, a chain that could at one time claim 95% of the US population lived within three miles of one of its stores, sadly closed down permanently in 2017.

Even so, the time in my life it represents, the sheer force of discovery it provided, the capabilities it displayed, the potential it showed, the experiences it allowed, even now as I get older it provides an incredible rush of nostalgia and reminds me of the excitement I felt for technology as it was a new and exciting thing in the consumer space. I don’t feel it so much these days, but at least there’s something that provides such a reminder.

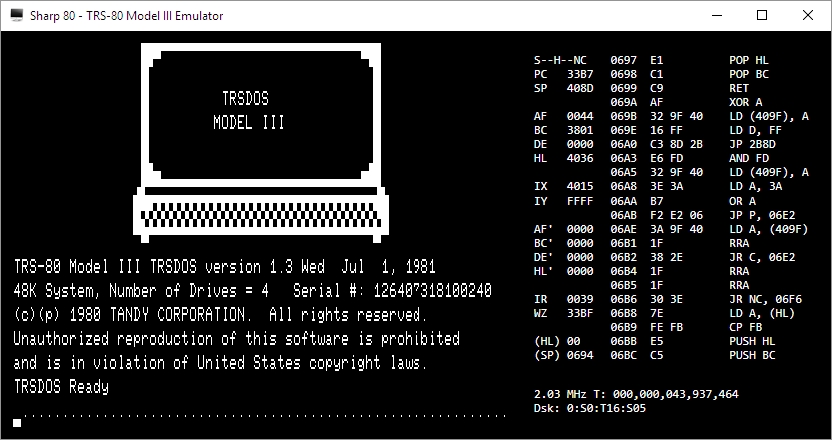

I am also happy to announce that there is a fully-functioning Windows-based TRS-80 emulator, Sharp-80. It works amazingly well and shows exactly what kind of interfaces and accessibility we had to work with back then. Be warned: It’s fun to use and of course I’ve spent a long time with it reminiscing about the bad old days, but it’s also not for the faint of heart, and if you’ve been raised in the coddled, cushioned world of GUIs, you’ll be in for a shock. A wonderful, text-based shock.

Happy birthday TRS-80, and thanks for everything. I’ll always remember.

A trip to the computer history museum

As a computer historian, I have – of course – always been a fan of the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. It’s a remarkable, amazing place, where you can see displays relating to things we are already familiar with: Things such as the evolution of the Internet and hypertext, a small display on gaming, as well as a slew of hardware, much of which I actually used at one point or another (Hello SGI workstation!).

There are also more eclectic displays, such as the one regarding the evolution of computer graphics and the hardware that created and displayed it (one more time: Hello SGI workstation!). Even the well-known Utah teapot that became a standard for computer graphics and animation has its own display.

A relevant side-note I should mention here: I’ve mentioned Silicon Graphics workstations twice now, and as fate would have it, The Computer History Museum itself is housed in the old SGI building. See how things come around?

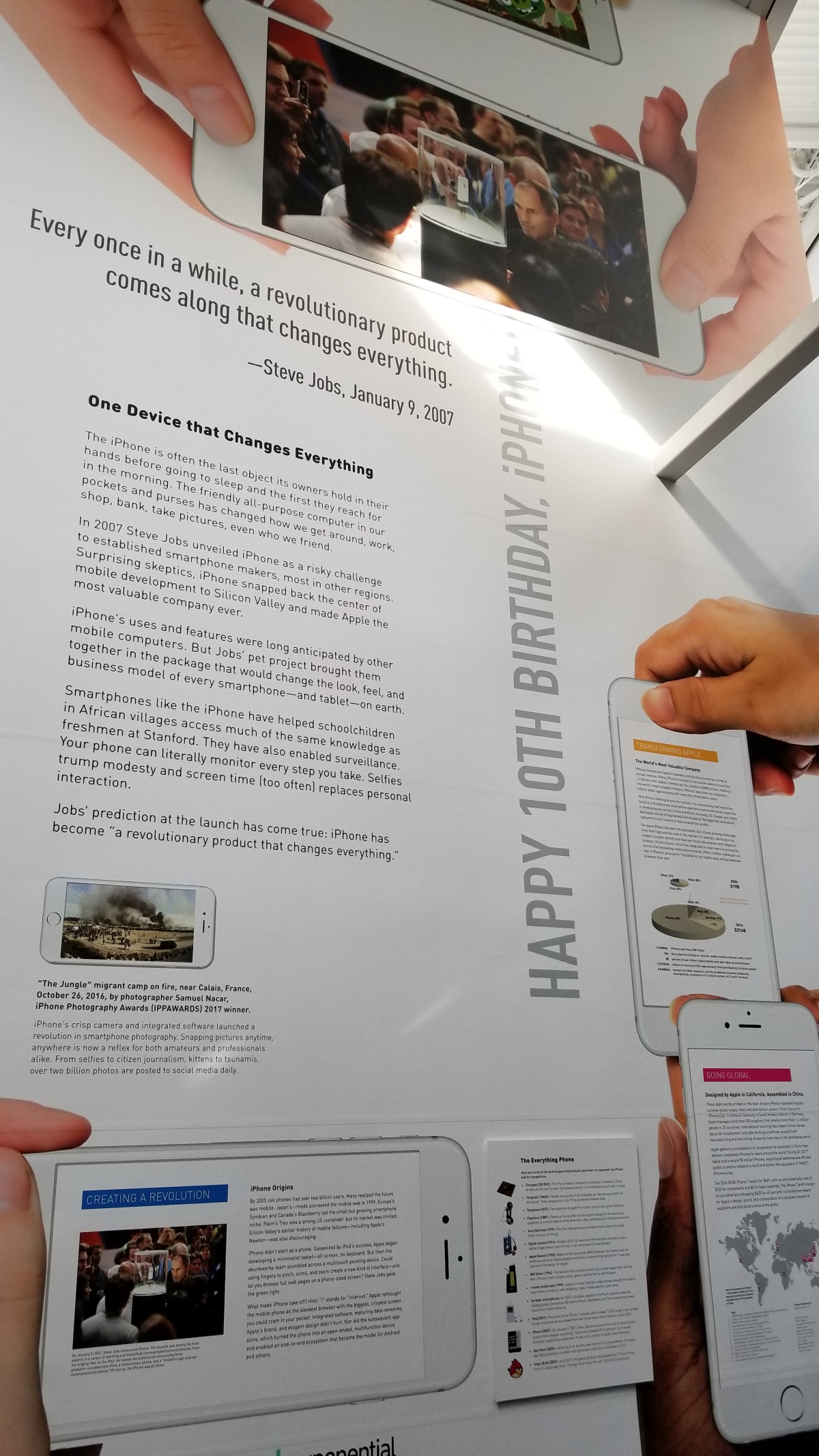

Right when you walk in , there is a huge display about the iPhone, and I was very impressed to see how fair it was; it sung the praises of it, while at the same time presenting some controversies surrounding it in a very balanced an forthright way. Kudos to them for that, I was impressed.

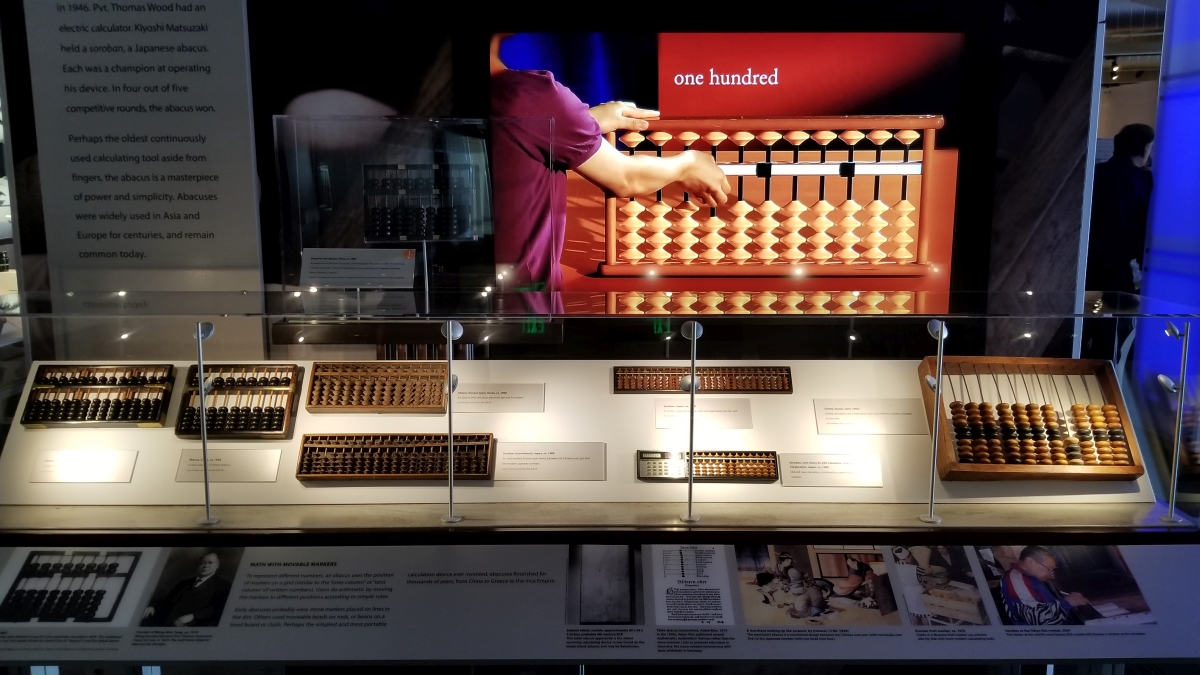

Its most interesting displays are, at least in my humble yet nonetheless correct opinion, the ones dealing with the real, wayback history, including things like an extensive display about the abacus, slide rule, and less-known analog computing tools such as Napier’s Bones, and there are more on offer. To the credit of those who developed and used these tools, they were not easy to use, and there are directions on how they worked for those who wish to give them a try.

Soon after your time in that room, you are then introduced to one of the most significant events in computing history, and one students in my Ubiquitous Computing course spend a whole week learning about: the creation of the Hollerith Tabulating Machine, developed by Herman Hollerith to compute data for the 1890 census. It was a huge success, both in terms of its function and design, and formed the foundation of what would later become IBM.

Soon after this exhibit come the computers of the 40s, 50s, and 60s, ones mainly used by governments and universities, and that often took up rooms of space thanks to their prodigious use of vacuum tubes. There were many, and there are many on display, some from companies well known and some from one-shot attempts. Below are pictures of the IBM 1403 mainframe, including tape drives and card reader/sorter, as well as what I feel is a pretty nifty image of the Johnniac tube array. Of course, the highlight of the display is their UNIVAC, to which mere photos could never do justice.

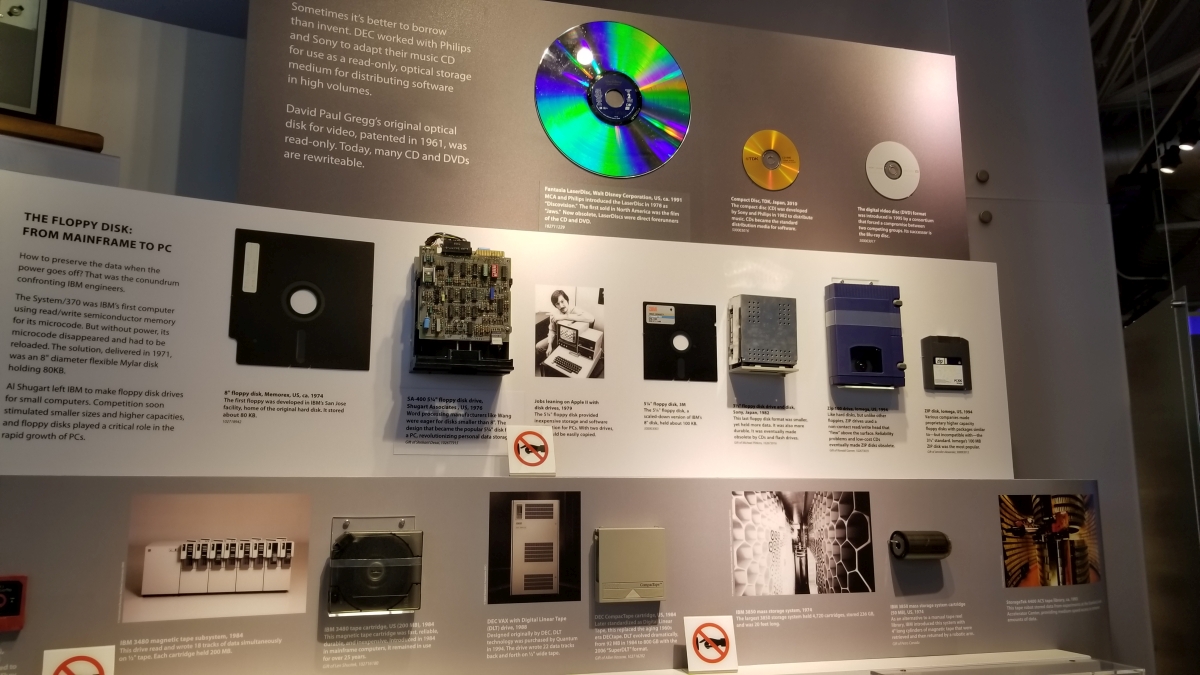

Another thing my Ubiquitous Computing (or Internet of Things, if we want to be familiar) students learn about is the evolution of storage, and the CHM doesn’t disappoint here either. Whether wire-wrapped core memory, or magnetic versus optical storage, the museum presents a very thorough look at how storage of all types has evolved from the very beginning.

One thing I found disappointing about the museum is their anemic display on gaming. It’s as cursory as it can get, with very few displays and nothing about the real history of the industry, something we spend weeks talking about in my game development course. Nothing about Adventure, an absolutely groundbreaking game that my students have to play and write a paper on, nothing about the defection of Atari employees because of atrocious company management, with said employees then forming Activision, the first third-party publisher that completely disrupted how games were made. It’s a minuscule display that fails gloriously at really discussing the history of gaming, and instead simply presents what appear to be random artifacts. It didn’t even warrant a picture.

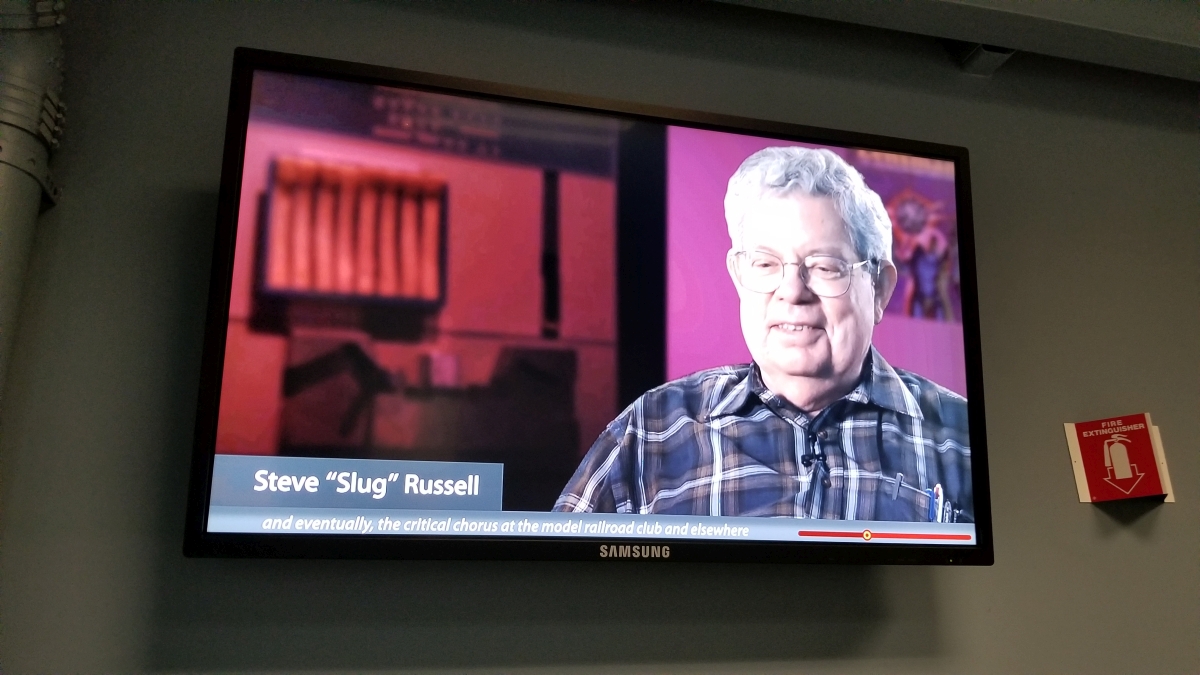

That being said, they do have a fantastic display of a PDP-1, the machine on which the very first computer game, Spacewar!, was developed. Additionally, they have a repeating video of Steve Russell, who developed the original, playing to educate visitors about how significant this was. Of course, if you took my class, you would know that he developed the base game, but others added additional features, such as a star map based on the actual sky, gravity, additional controls, and so on. It’s humbling to see, and since back then computer companies sold hardware while giving software away for free, the game garnered a lot of attention as PDP mainframes were, comparatively, used a lot by people who would be interested in something like that (about fifty were made, but they all had Spacewar!). Also, just to clear up any potential confusion, the exclamation point in Spacewar! is actually part of the title. If you’re interested in giving it a try, you can play a faithful HTML5 version at this link.

The museum has a ton of exhibits, from the Altair that Bill Gates wrote his company’s first program for, to the first Apple computer signed by Steve Wozniak, to consumer robots over the years, to a Commodore Pet (the computer on which I first learned programming), even an Enigma machine! If you’re interested in the history of technology and computing, it really is a fascinating place, covering the earliest attempts at computing to the future and beyond. From the first transistor to the Xerox Alto with the first GUI to the Cray mainframe and a ton of other great stuff, have a look at the pictures in the album below and see some of the fascinating displays on offer.

On this day, the TRS-80 was born!

Today, August 3rd, is the 40th anniversary of the TRS line of PCs, manufactured by Tandy and sold through Radio Shack.

Ah, Radio Shack. My eulogy for your passing continues to this day. When you were actually a ‘radio shack,’ a place I could go to buy electronics, transistors, capacitors, soldering irons, when you catered to the people who made you what you were. At one point, Radio Shack was so ubiquitous, one could be found within three miles of almost all American households. Now, however, they were reduced to this before disappearing completely. Even with 70 stores apparently remaining, for all intents and purposes it is gone, considering it lost its way and identity long ago.

But I remember quite fondly the Radio Shack of yore. When I started college at my mostly-beloved Alma Mater UMBC, my significant other at the time worked at a Radio Shack right around the corner. They sold electronics for real enthusiasts and hobbyists, and even PCs from their Tandy line. Tandy, a leather company that still exists today, bought the struggling Radio Shack back in the 60s in attempt to diversify. In fact, the TRS portion on many of their computer model names was an acronym for Tandy Radio Shack. It was glorious for me to go in to the store on a dark and snowy winter night, when the store was open but no customers were about, to play Space Quest One on one of the Tandy machines they had on display.

But my affinity for the TRS line goes back much, much further than that. I actually learned to program, using line-number basic no less, on a TRS-80 model III. I actually took programming classes using this machine, which would have been around 1981 or so. Normally I would just hyperlink to a page about it as I have indeed done, but I feel it is important enough that I must also include an image whose glory in which you should bask (The header image is a Model III as well).

Isn’t it beautiful? It was a great machine for the time, with a speedy 2MHz Zilog processor, the same one found in all TRS-80 desktop models, however its 4K of ram could be boosted to 48K which was ludicrous overkill at the time. Even though it had dual disk drives, which was a feature shared by the Apple IIe, it also had external cassette storage, which is what I mainly used. $600 would get you the whole shebang, cassette storage and monitor included.

I also find it strange that model numbers are often left off when people describe these machines. Earlier models had all components as separate items, and less memory, and a slower processor, and reduced functionality. When referring to the TRS-80 line, the model number is very important.

I programmed my first game on one of these very machines, a model III. It was a text adventure through a haunted house from which you were trying to escape. You had to find items, using some and combining others. I even went out of my way to have everything make logical sense, if not be overly challenging; for example, at one point you come across a skeleton who is searching for his lost femur. You later discover a dog trying to bury a bone. Hmm. I must say it was pretty fun! I would save the code to cassette – that’s right, audio cassette – and load it to play or edit. It was also because of that that I learned another valuable lesson which was not taught in programming classes at that time: save your work. You see, to save onto a cassette, you had to manually wind the tape past the leader tape that was not magnetic and can’t hold data, or else the computer would try to save some of what you were doing to that, and the whole thing would fail, of course.

Valuable lesson to learn, that.

So it bears repeating: as the headline states, the reason I am telling you all about one of my favorite vintage PCs (an honor shared with the Commodore Pet and Apple IIe), is because today, August 3, is the anniversary of the TRS line of PCs! They were first announced in 1977. This is one of the machines that had a major impact and influence on me, and amplified my love of and interest in technology. I’d like to get one and do some tinkering once again. Unfortunately, TRS-80s have also, along with others including the aforementioned Commodore Pet, become sad victims of the Ebay economy, in which everything is worth a fortune if you’re selling it on Ebay. Here’s the going rate for a Model III, which isn’t as bad as it has been in the past (remember this post from 2014? Of course you do!). For good measure, here’s a Commodore Pet and an Apple IIe.

Even so, I’ll keep an eye out for a chance to relive my childhood, and celebrate this day. If anyone finds one cheap, let me know!

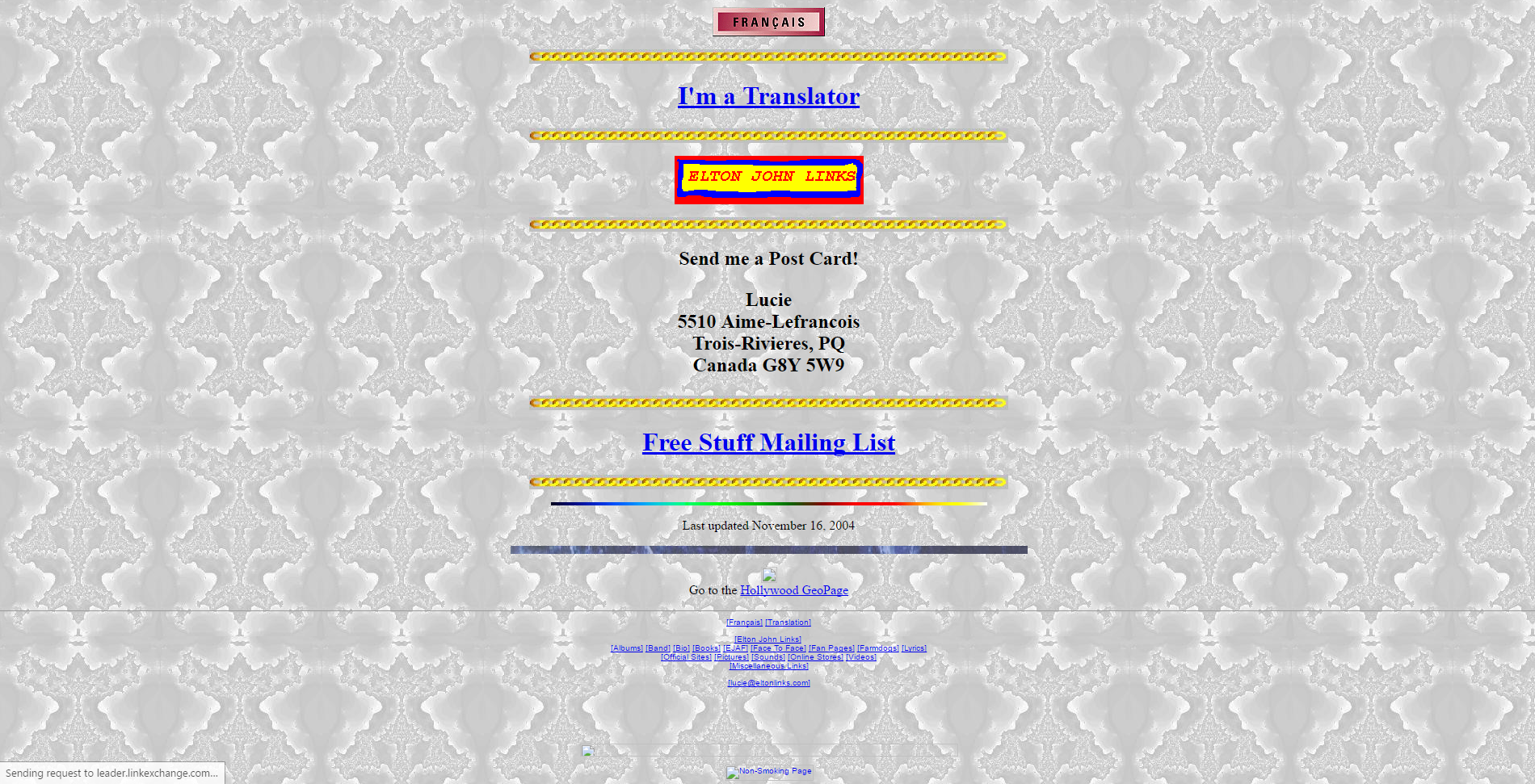

Journey with me back to the early days of the Internet with ReoCities, the GeoCities archive

In my graduate design class this week, the additional discussion topic (bonus, as I refer to it, although I suspect my students might disagree) involves the attempt to archive one of the early web’s most important communities. Indeed, I wanted to go back in time to the early days of the World Wide Web, circa 1993, and as a technology historian, indulge that aspect as well. The Internet, like me, was brought online in the glorious year of 1968, however it remained the domain of scholars and governments for over two decades before becoming available via the World Wide Web to the riff raff public and its clammy tendrils (by the way, ‘Internet’ is always capitalized, regardless of what the Oxford English Dictionary says). Remember also that the Internet and the WWW are not the same thing; the Internet is the technologies, hardware, software and protocols on which the web sits – the Web didn’t come online until around 1990. Getting back on track, to say design was at its nadir at that point would be a severe understatement; while interaction methods had been developed and attempted over the years (light pens, for example), that was by specialists in specific domains, and when I say specialists I don’t mean interaction specialists, I mean engineers and programmers, but now web design was about to be attempted by everyone.

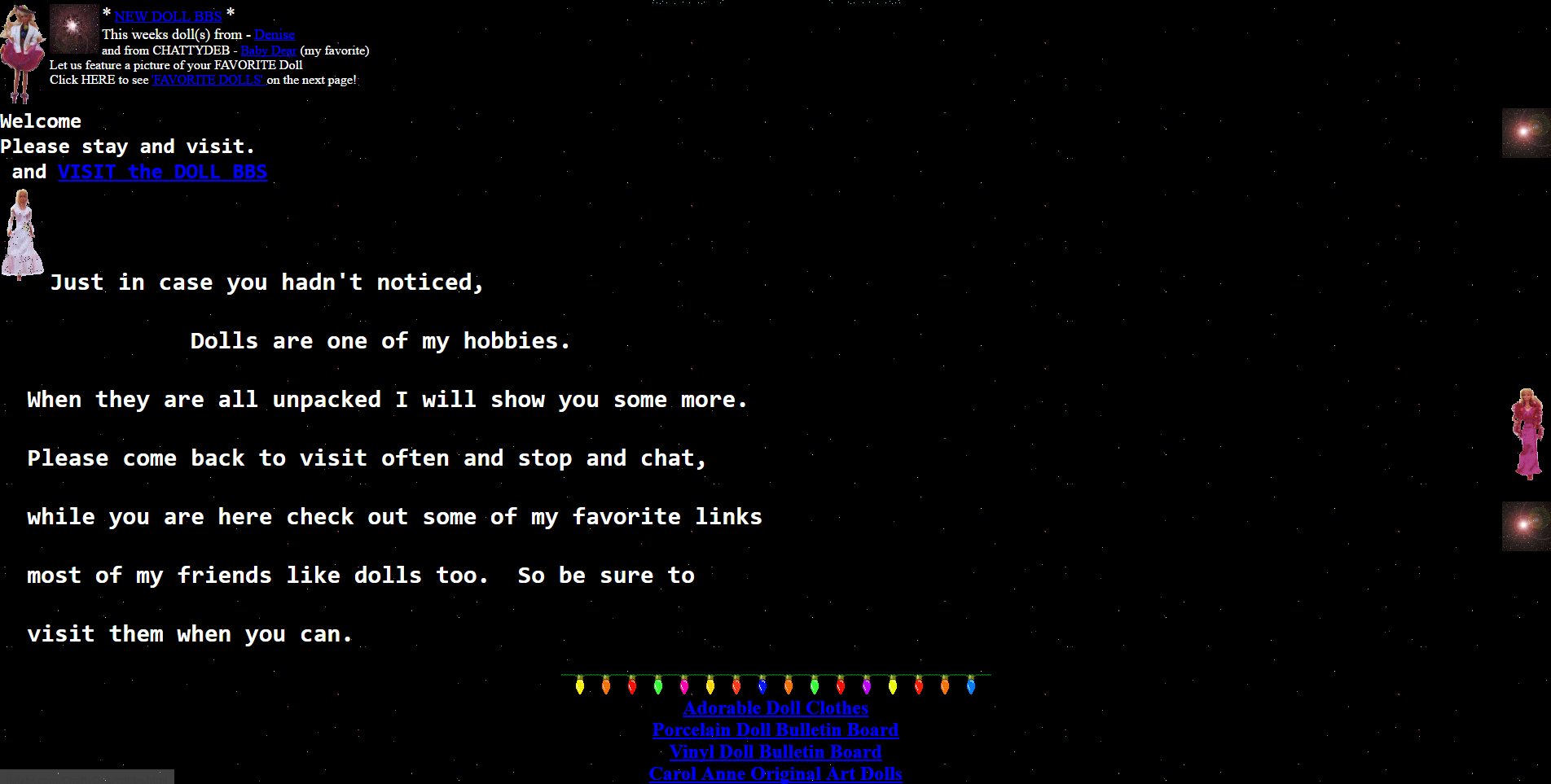

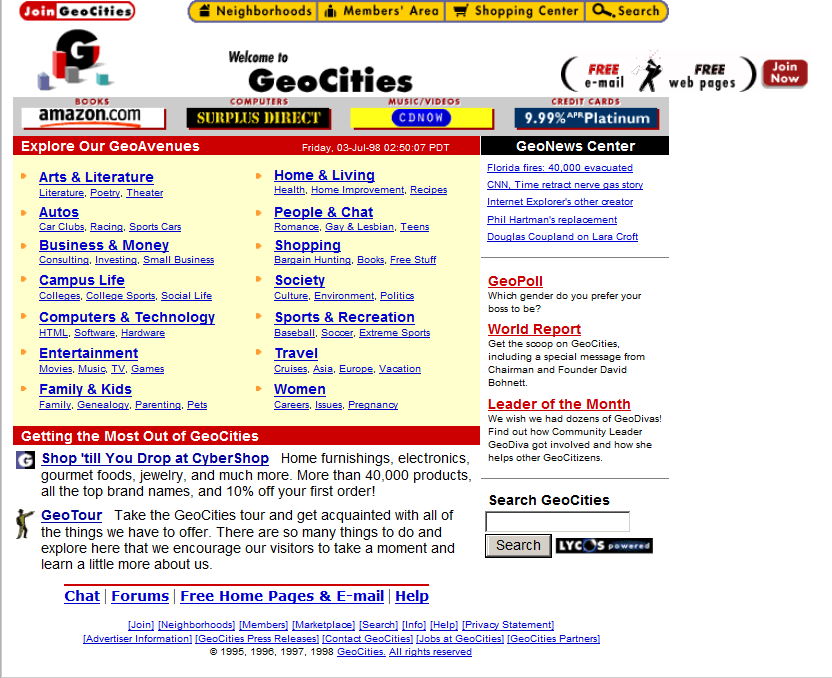

When everyday people began to experiment with what the Web offered, they did so from an adventurous, new, exciting perspective. Interaction methods, organizing elements, color, layout, usability, nobody cared about this stuff, we were amazed at the accessibility of it all. We hadn’t even learned it was bad form to hotlink images! Almost none of the technologies, platforms, infrastructure, anything, really, we have today was available back then other than base protocols, and even those have evolved significantly. But one thing we did see, very early on, was a foreshadowing of the idea of a web 2.0, in which user generated content and communities guided the growth of one particular website far beyond what anyone expected. Before the design disaster that was MySpace, anyone who was anyone cut their teeth on GeoCities.

Everyone knows GeoCities was the equivalent of a design traffic accident with its animated gifs and auto-play MIDI tunes (and was the inspiration for the landing page for this very course), but that’s looking at it through the-opposite-of-rose-colored glasses. We know that *now.* Back then, the ability for anyone to have a presence online and represent yourself immediately all over the world was almost too much to process. No one cared about design, they just wanted to create. As anyone now looking at a GeoCities page could tell you, design would come later. Much later.

GeoCities divided their content up into towns, each of which represented a particular interest. Whether it was fantasy, health, sports, the arts, or whatever else, there was a neighborhood for it where a community of like-minded individuals could set up a shingle, as it were, and have a presence…perhaps even make some new acquaintances or even friends with the same interests.

The site’s growth and eventual buyout by Yahoo and unavoidable death is beyond the scope of what is intended to be a design history, however it is a fascinating story and very interesting if you get the chance – you can read about it on this Computer History Museum page (look at that GeoCities landing page!).

Instead, this long narrative is to let you know that you can still experience GeoCities in all its poor-design glory thanks to the project known as ReoCities. They have archived millions of pages from GeoCities, and while the usability leaves a lot to be desired, it is a fascinating look at web design back then, and looking back through time at these pages I feel like an astronomer looking back in time at a star. It gives a frozen-in-time glimpse into not just where we were, but how far we’ve come. I used ReoCities for all the screenshots in this post.

I have to be honest, some of the pages are difficult to view, the design is that wacky. In terms of expression, in terms of digital explorers mapping out a new, unexplored land, however, it’s mesmerizing. I can’t tell you how long I spent not only exploring the myriad pages archived by the service, but seeing how many of the external links still worked (not many, although some GeoCities page redirect to a proper hosted site; very smart), and even doing some research to see if any of the people or organizations are still around and updated their web presence. It was a pleasant surprise to see some of them actually had!

It’s a really fascinating time capsule not just of early web design, but also of where the web was its infancy. Seeing how design has changed, what was considered acceptable design back then versus now when we have so many rules and standards and guidelines is enlightening. And if, on the off chance, you have a link that points to a GeoCities site that they’ve archived, a simple letter change can update your link!

I’m a big fan of historical preservation of digital property (archive.org is another glorious monument to what was). Start your wayback voyage to GeoCities over at ReoCities.

It’s all gone

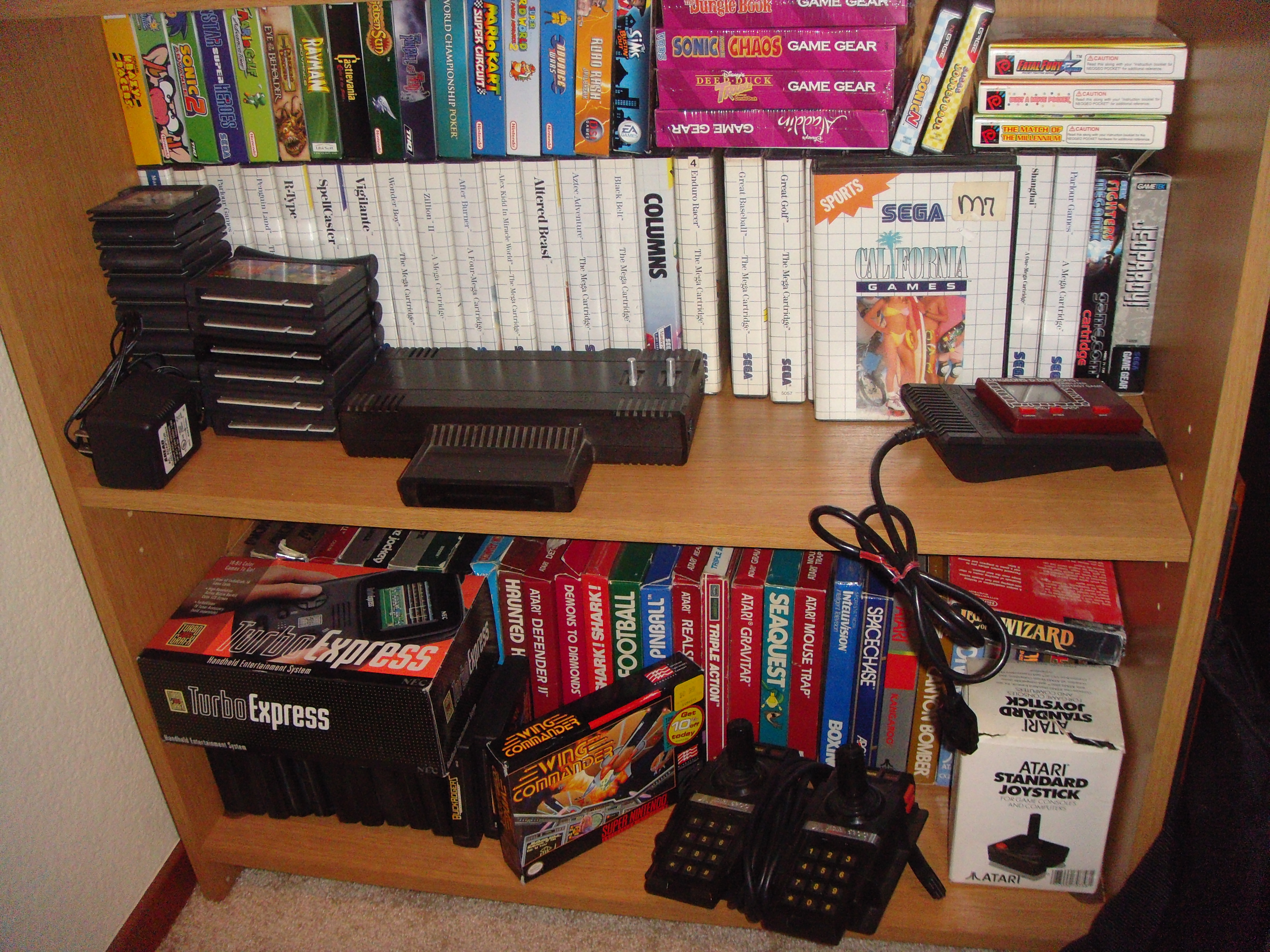

(UPDATE: Many more pictures of the collection itself and some additional narrative can be seen at this Imgur post)

Actually, it’s not really gone, it’s just gone to a better place. It was finally time. I have donated my entire 40+ year collection of video games, consoles, manuals, displays, advertising and other miscellany to the Transformative Game Lab in the Department of Informatics at The University of California, Irvine.

I had been thinking about what to do with it all for a number of years. I have been collecting these things for decades, and while I love them all, most of the collection has been sitting in a garage in Las Vegas for the past six or so years, baking summer after summer in the brutal Vegas heat.

I wanted it all to go somewhere where it would be of benefit and use. Somewhere where it would be appreciated, where the games would be played and the manuals read, where they would be studied and researched as the works of art they are. I had thought about willing them to the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester NY, however the problem there is I would have to be dead to see my dream realized.

While I was thinking about it, I took a position in UCI’s Department of Informatics, where I learned quickly they do games research, they have a game lab, and most importantly of all, they consider it a valid field of study and give it the respect it deserves. I spoke with Joshua Tanenbaum, the professor who heads it all up, and serendipitously it turned out he was looking to expand the lab into retro gaming! An earlier attempt at getting an eBay seller to donate his collection hadn’t worked out, and although my collection was nowhere near what that seller had, we both knew this would still work out perfectly.

It wasn’t easy. My collection is big and random. It didn’t lend itself to easy packing and storing. Having sat in the garage all these years, it was also covered in a layer of dust, not to mention spider webs, dead bugs, and other detritus that is unpleasant to say the least. Having lived in Vegas for so long cleaning it up wasn’t a problem, but it was a big part of the project. Not to make anyone uncomfortable, but here is a picture of one of the webs when I first opened the garage door. You can also see in the background how disorganized it all is. Under that is a (poor iPhone) pic from the other end. It’s the loosest, most disorganized collection you can imagine.

Even my beloved Genesis Collective went into the donation. I was surprised to receive some backlash from friends and family over that, and resistance to it. I didn’t realize how important it was to not just me, but others as well. Although it may seem counter-intuitive, that reinforced my belief I was doing the right thing, that they held meaning and importance and needed to be somewhere they were appreciated.

Also, meet Walter.

As is true of any collector, however, I had some duplicates, and it turned out my friend only wanted Aladdin anyway, so I have already restarted the collection and they got what they really wanted. Win-win!

There was much more than that, of course, so here are some non-exhaustive pictures of the other fun stuff that was donated. From the top: Sega Dreamcast (and some PS2) games, Sega Master System/Jaguar/Atari 5200/Sega Game Gear titles, Nintendo Virtual Boys (also notice the adults-only Mystique titles for the Atari 2600 on that lower right-hand shelf), and PC games.

It took days to get it all packed up. And when it was, it was just as chaotic as before. There was simply no way to organize everything into a cohesive package, and I gave up on the idea pretty early in the process.

Here’s how it looked when all packed and ready for loading into the U-haul.

There’s a lot there. The next step was to finally load it all into the U-haul. My dad flew in from Central California to help, and my dear friend Shauna even pitched in.

It was so hot on loading day (105 degrees, which for Vegas is actually considered a cooldown) that when the truck was finally loaded with boxes and other fun stuff, we had to leave the door propped open or it would have roasted the contents beyond repair. We left it open for about 4 hours, until around 7, until it was cool enough to finally close it up.

The next morning at 6am, we were off.

It’s a long, mostly uneventful drive through the desert and down the 15 until you hit SoCal, but I like the desert and its vast open plains. We saw the massive reflector fields, formally known as the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System, near Primm, and this picture is only one of them. They’re an impressive thing to see!

And to be fair, when you’re driving through the desert, EVERY road is a ghost town.

We arrived at UCI around 11:45, and began the unloading process. Josh Tanenbaum, who I introduced earlier as the main man doing game studies in the department was there, as well as just-hired Aaron Trammell and others who agreed to pitch in. While it took three and a half hours hours in the blazing heat to load the truck in Vegas, with the help of 10 people it took about ninety minutes in not-too-bad heat to unload, and that even means carrying everything – including three arcade machines – to the sixth floor and through a labyrinthine maze of doors and halls to get to their final resting place. Well, it’s not actually their final resting place, but they’ll all be here for a while until we find them a permanent home in the building. Thanks to Josh for providing these pictures, as I was too exhausted and excited and neglected to take any!

The first is the truck right before unloading, the second and third are a couple of celebratory poses after a job well done, and the rest are some pictures of the room after it was all loaded.

To say it’s bittersweet is an understatement. I have carried some of these items with me for what seems like my whole life, having received them as birthday or holiday gifts when I was still in the single digits. I distinctly recall the specific moment when I acquired many of these things, whether it was the subpar Fighting Masters for the Genesis I picked up at the Annapolis Mall in Maryland or the Genesis collection I found in a flea market in Edmonton, Canada; Adventure for the Atari 2600 I received for my Bar Mitzvah at 13 or the ColecoVision controllers I had to wade through a warehouse in a seedy part of Baltimore to find. The Atari Lynx games I’d buy at the very same Toys ‘r’ Us at which I worked or first discovering the original GameBoy, each one carries significant memories with it, and it’s all a major part of my life. I did not give it up lightly.

I by no means have lost interest in the hobby, I’m still very much interested and very much vested, however changes have occurred both within and without the industry that moved me in this direction, however those are issues for another post. I would just like to say PC Master Race. PC MASTER RACE! Also, Steam, GOG, and emulation (don’t judge!).

I kept a couple of things. A Dreamcast VMU that has a fully unlocked Hydro Thunder Save, The World of Warcraft server (Bloodscalp) I used to play on, a soundtrack for the PlayStation title Road Rash: Jailbreak that my band was featured on, and the promotional Christmas Nights Into Dreams for the Sega Saturn. But everything else went in the truck.

At the same time, I have no regrets and had no hesitations. Where the collection is now is where it belongs – with people who will truly appreciate it, where it will be treated with dignity and respect, where it will be used and enjoyed. It wasn’t right to keep it in the garage for years on end, and although they’re just inanimate objects, well, I think they’re happier here, and we all are, too.

As the collection is inventoried and catalogued, as a final location for its display and use is selected and brought online, as the catalog and apps and everything else are created, and as any other milestones are reached, I’ll post updates. I’m excited for the future of it all.