The Lawnmower Man, and Vintage CGI

Inspired by a couple of Reddit forums to which I am subscribed, VintagePixelArt and VintageCGI, and being a fan of all things historical as it pertains to technology, I uploaded to the latter a brief scene from the 1992 CGI-fest movie The Lawnmower Man,’ supposedly about a guy who killed people using a lawnmower. Based on a book of the same name by Stephen King, King sued to have his name removed from the movie as it bore – barring one minor scene – absolutely no connection to the book. Rather, the movie was used as a vehicle to show off what the state of CGI, or Computer Generated Imagery, was at the time. The 30-second plotline is Dr. Angelo, a scientist funded by a shadowy company, is researching whether or not Virtual Reality can be used to enhance the human cognitive capabilities, or even unlock potential powers. He recruits Jobe, who helps around the grounds at local church and suffers from cognitive disabilities, and straps him into a complicated VR setup that turns Jobe into a god who ends up not acting very godlike.

The movie was fun, but the real purpose of the thing was to show off what the state of the art was in terms of CGI at the time, and also present what was at that time a still-unknown technology: Virtual Reality. Here is the clip I uploaded; I just clipped the scene out of the movie file:

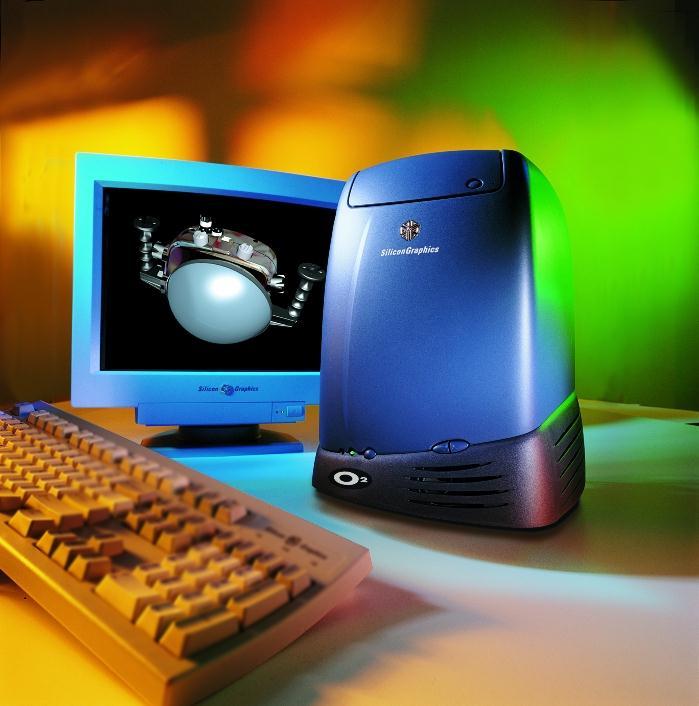

In 1992 when the movie was released, commercial-grade computer generated imagery was created primarily on Silicon Graphics workstations, which at the time were the powerhouse machines of the day. Now, we have laptops with more computing power, but back then SGI workstations were the top of the line pro setup, and everyone from movie studios to science labs to government agencies wanted them for their ability to do everything we take for granted today: Simulations, animations, visual manipulation, prediction, etc.

They didn’t necessarily use special processors or OSs, in fact many of them ran on Intel processors and Windows NT, although other versions ran on UNIX. The difference was their proprietary hardware architecture, and compared to what commercial PCs had at the time, the SGIs were far more powerful. $4,000 would get you their low-end model: a Pentium II-powered box with 128MB of RAM. You read that right. This is a Linux box SGI, the O2:

Appropriately, the former SGI building in Santa Clara now holds the Computer History Museum.

Movies were used as vessels to show off incredible, and sometimes not so incredible, computer imagery quite often. The absolute king of the hill in this area is the original TRON (1982), which not only used CGI but many other tricks as well, and gave us a glimpse of what life might be like inside a machine when computers and technology were still largely undiscovered country but arcade machines had already left an indelible mark. A perfect example of TRON’s influence is in the famous light cycle scene.\

The first ever use of CGI in a movie was all the way back in 1976’s Futureworld. This movie used a scene of a CGI hand that had originally been developed by Ed Catmull, a computer scientist at – wait for it – teh University of Utah (see below) who went on to create Pixar! Here’s the scene from Futureworld.

Computer capabilities in terms of imagery, visualization and rendering has been the fascination of many for a long time. One image has even gained celebrity status: The Utah Teapot. (Side note: I usually prefer not linking to Wikipedia, however the University of Utah’s own Utah Teapot page links there!).

The Utah Teapot, created in 1975 based on the need for a perfect shape, has since become the introduction to computer graphics, and has been featured extensively in other computer animated environments, with my personal favorite of course being its appearance in the animated sequence from The Simpsons’ Treehouse of Horror episode, titled Homer(3), in which Homer gets sucked into the horrific THIRD DIMENSION. You can see the teapot at 2:21 when Homer realizes he is ‘so bulgy.’ There are many other neat references in the scene. This scene was based on an episode of The Twilight Zone, a prophetic show in and of itself, called ‘Little Girl Lost,’ in which a girl is transported to the fourth dimension from the third.

Because we didn’t have immediate access to the capabilities of technology back then, especially computer animation, seeing it was a revelation. This was capitalized on by a series of (originally) DVDs, later laserdiscs, titled ‘The Mind’s Eye (1990).’ The followups were Beyond the Mind’s Eye (1992), Gate to the Mind’s Eye (1994), and Odyssey Into the Mind’s Eye (1996). Each was about an hour long and contained a series of CGI vignettes set to music. These vignettes were created by graphics firms, advertising firms, and others, and often scenes created by different companies were woven together and set to music to tell a story.

I first saw a scene from The Mind’s Eye being displayed on a giant display TV in front of a store (I don’t even remember which store!) in Security Square Mall in 1990, and I was mesmerized. I should have been amazed by the TV, but it was the visuals on it that really blew me away. It’s not my favorite scene in the series, but it holds a special place in my heart for introducing me to the series and for telling a touching story to boot, about a bird and a fish that destiny has deemed will be together. A hopeful allegory for today. Here it is:

I can’t find any information about who actually created this animation, so if you know, please pass it on! You can also watch the entire movie on The Internet Archive.

My favorite scene from the Series is found on the Second release, Beyond the Mind’s Eye. This one is called ‘Too Far’ and contains multiple scenes from various artists, including what might be my favorite animated character ever, the once famous Clark. There’s a lot going on in this segment, and it’s a masterpiece of CGI of the time.

Now here’s where it all ties together: The CGI created for the Lawnmower Man was also included in scenes from Beyond the Mind’s Eye. Not only that, the movie’s CGI was created by Angel Studios, which would later become part of billion-dollar video game powerhouse Rockstar San Diego. See how it all comes together?

In the years that followed, machines like the Amiga and of course Macs and PCs overcame the need for dedicated workstations, although the term persists. And now easy access to all sorts of graphical capabilities is at our fingertips, with engines being able to calculate what we can see and what we can’t and render accordingly, or cast rays of light based on reflection and refraction, or apply textures to surfaces, and so on. But that’s what makes these creations so much more impressive; using the tools of the time, they still were able to create such magical animations.