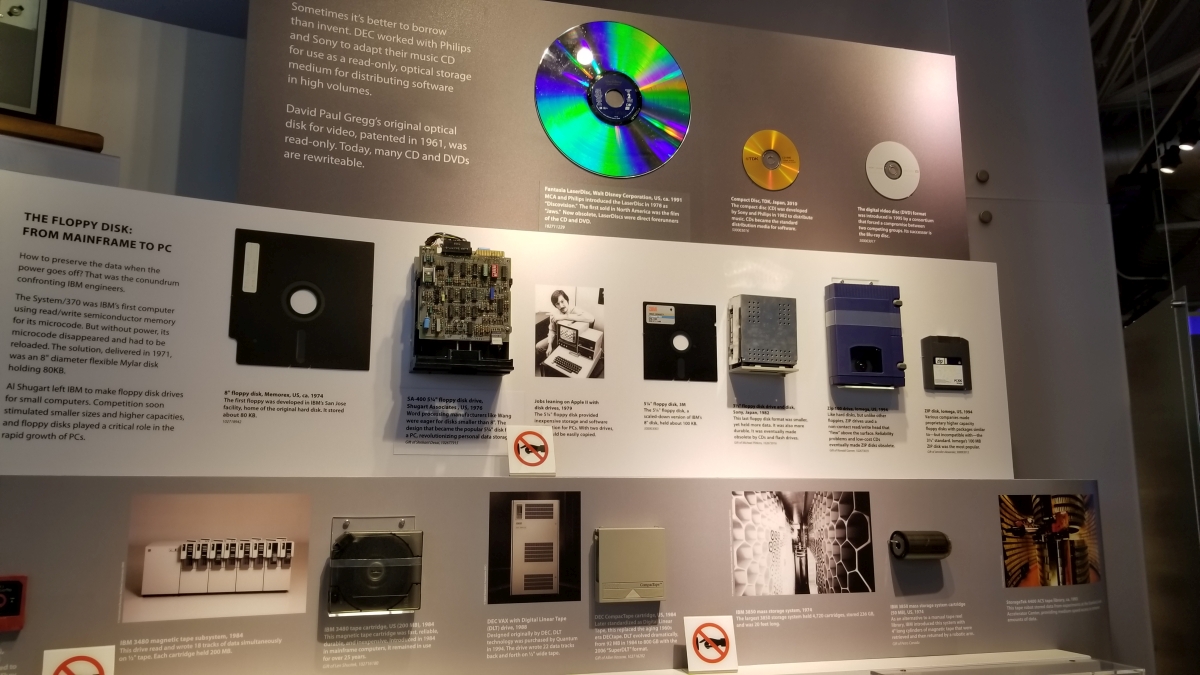

A trip to the computer history museum

As a computer historian, I have – of course – always been a fan of the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. It’s a remarkable, amazing place, where you can see displays relating to things we are already familiar with: Things such as the evolution of the Internet and hypertext, a small display on gaming, as well as a slew of hardware, much of which I actually used at one point or another (Hello SGI workstation!).

There are also more eclectic displays, such as the one regarding the evolution of computer graphics and the hardware that created and displayed it (one more time: Hello SGI workstation!). Even the well-known Utah teapot that became a standard for computer graphics and animation has its own display.

A relevant side-note I should mention here: I’ve mentioned Silicon Graphics workstations twice now, and as fate would have it, The Computer History Museum itself is housed in the old SGI building. See how things come around?

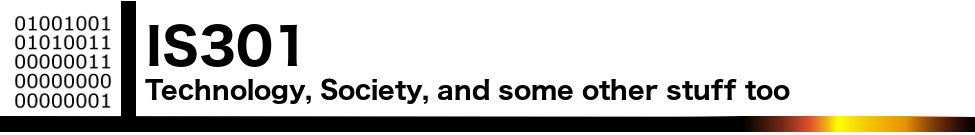

Right when you walk in , there is a huge display about the iPhone, and I was very impressed to see how fair it was; it sung the praises of it, while at the same time presenting some controversies surrounding it in a very balanced an forthright way. Kudos to them for that, I was impressed.

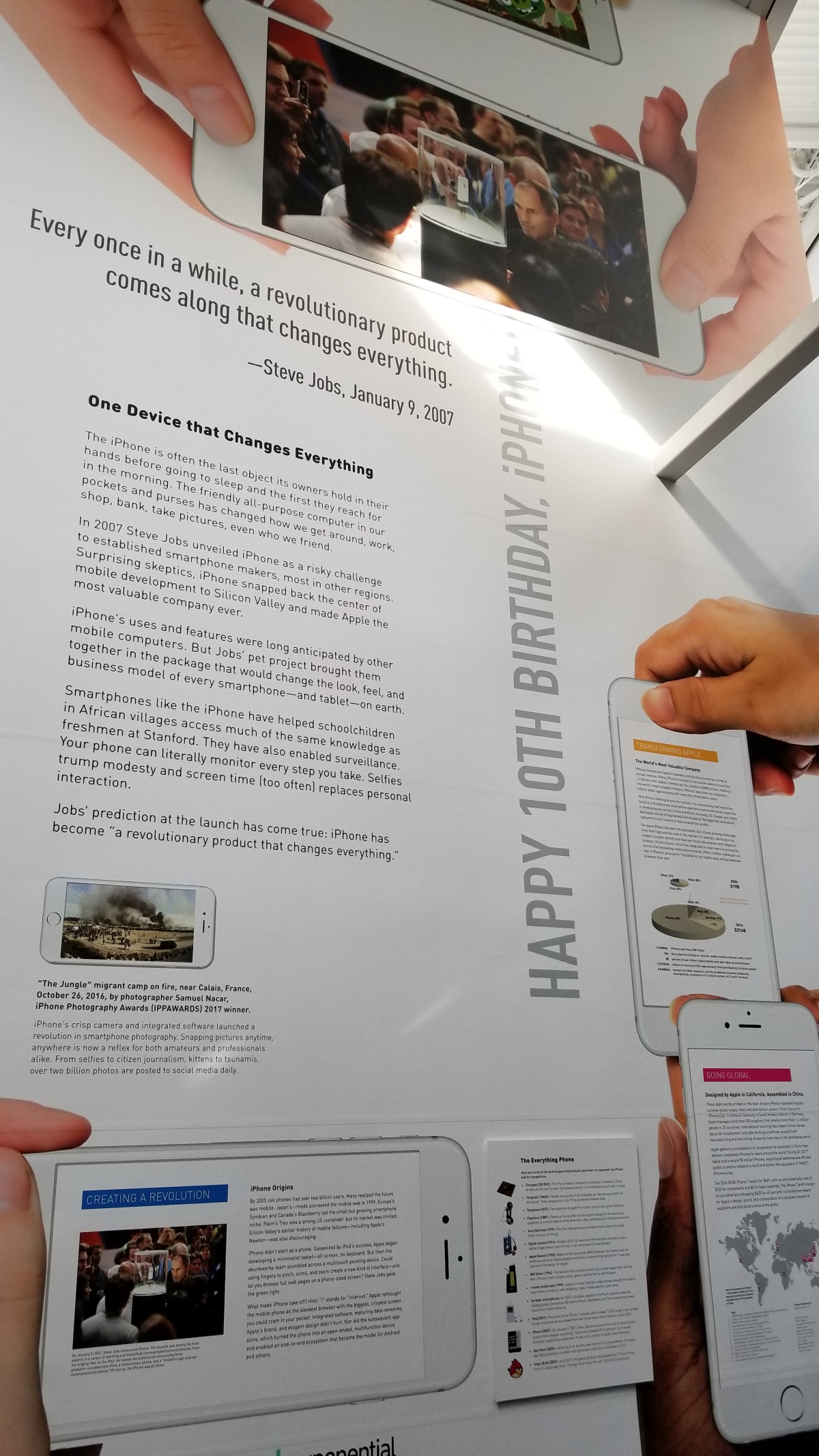

Its most interesting displays are, at least in my humble yet nonetheless correct opinion, the ones dealing with the real, wayback history, including things like an extensive display about the abacus, slide rule, and less-known analog computing tools such as Napier’s Bones, and there are more on offer. To the credit of those who developed and used these tools, they were not easy to use, and there are directions on how they worked for those who wish to give them a try.

Soon after your time in that room, you are then introduced to one of the most significant events in computing history, and one students in my Ubiquitous Computing course spend a whole week learning about: the creation of the Hollerith Tabulating Machine, developed by Herman Hollerith to compute data for the 1890 census. It was a huge success, both in terms of its function and design, and formed the foundation of what would later become IBM.

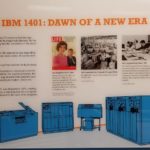

Soon after this exhibit come the computers of the 40s, 50s, and 60s, ones mainly used by governments and universities, and that often took up rooms of space thanks to their prodigious use of vacuum tubes. There were many, and there are many on display, some from companies well known and some from one-shot attempts. Below are pictures of the IBM 1403 mainframe, including tape drives and card reader/sorter, as well as what I feel is a pretty nifty image of the Johnniac tube array. Of course, the highlight of the display is their UNIVAC, to which mere photos could never do justice.

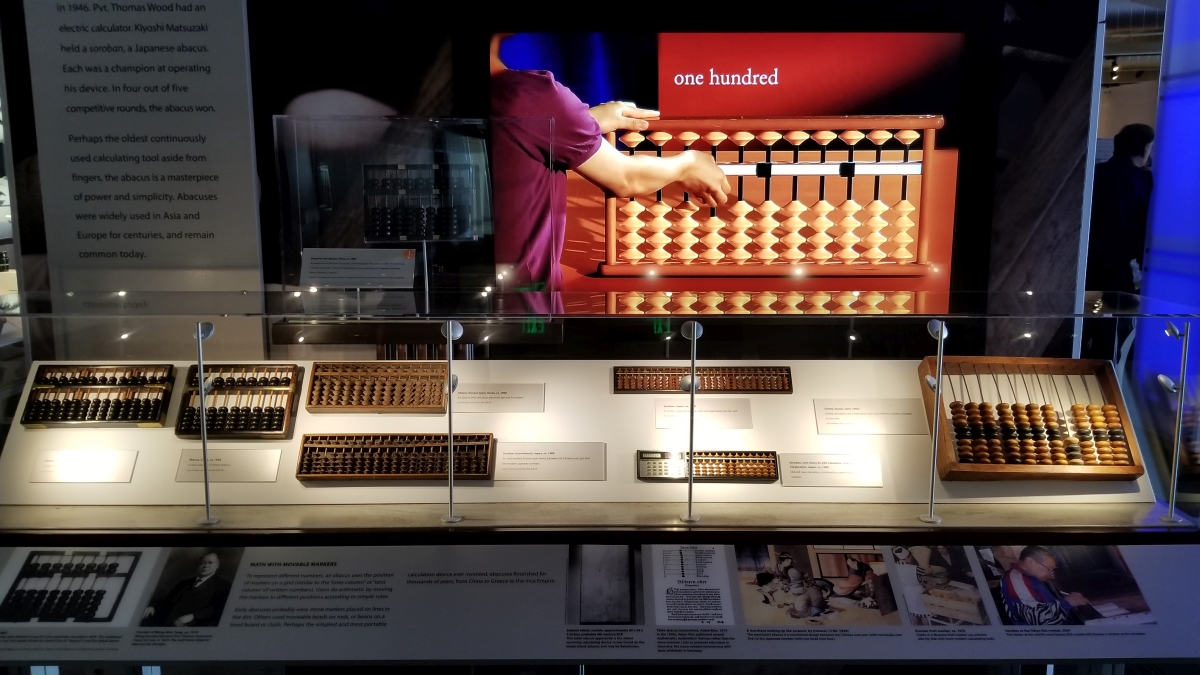

Another thing my Ubiquitous Computing (or Internet of Things, if we want to be familiar) students learn about is the evolution of storage, and the CHM doesn’t disappoint here either. Whether wire-wrapped core memory, or magnetic versus optical storage, the museum presents a very thorough look at how storage of all types has evolved from the very beginning.

One thing I found disappointing about the museum is their anemic display on gaming. It’s as cursory as it can get, with very few displays and nothing about the real history of the industry, something we spend weeks talking about in my game development course. Nothing about Adventure, an absolutely groundbreaking game that my students have to play and write a paper on, nothing about the defection of Atari employees because of atrocious company management, with said employees then forming Activision, the first third-party publisher that completely disrupted how games were made. It’s a minuscule display that fails gloriously at really discussing the history of gaming, and instead simply presents what appear to be random artifacts. It didn’t even warrant a picture.

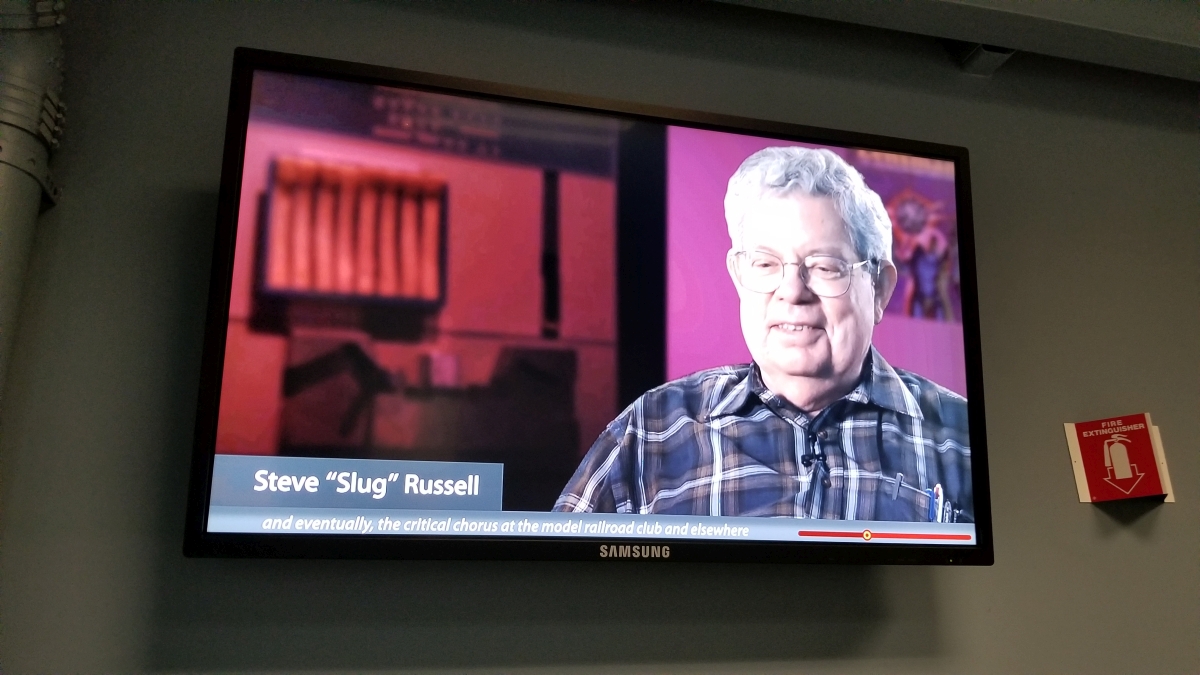

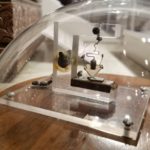

That being said, they do have a fantastic display of a PDP-1, the machine on which the very first computer game, Spacewar!, was developed. Additionally, they have a repeating video of Steve Russell, who developed the original, playing to educate visitors about how significant this was. Of course, if you took my class, you would know that he developed the base game, but others added additional features, such as a star map based on the actual sky, gravity, additional controls, and so on. It’s humbling to see, and since back then computer companies sold hardware while giving software away for free, the game garnered a lot of attention as PDP mainframes were, comparatively, used a lot by people who would be interested in something like that (about fifty were made, but they all had Spacewar!). Also, just to clear up any potential confusion, the exclamation point in Spacewar! is actually part of the title. If you’re interested in giving it a try, you can play a faithful HTML5 version at this link.

The museum has a ton of exhibits, from the Altair that Bill Gates wrote his company’s first program for, to the first Apple computer signed by Steve Wozniak, to consumer robots over the years, to a Commodore Pet (the computer on which I first learned programming), even an Enigma machine! If you’re interested in the history of technology and computing, it really is a fascinating place, covering the earliest attempts at computing to the future and beyond. From the first transistor to the Xerox Alto with the first GUI to the Cray mainframe and a ton of other great stuff, have a look at the pictures in the album below and see some of the fascinating displays on offer.